Blood draws are no fun. They hurt. Veins can burst, or even roll—like they’re trying to avoid the needle, too. However, clinical trial protocols often include instructions for regular blood draws throughout the course of a study.

Principal investigators for trials and doctors in regular clinical practice use blood samples to check for biomarkers of disease, including antibodies that signal a viral or bacterial infection, such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, or cytokines indicative of inflammation seen in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and sepsis.

These biomarkers aren’t just in blood, though. They can also be found in the dense liquid medium that surrounds our cells, but in a low abundance that makes it difficult to be detected. Until now.

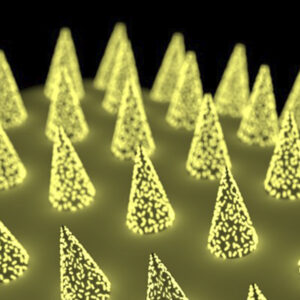

Engineers at the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis have developed a microneedle patch that can be applied to the skin, capture a biomarker of interest, and, thanks to its unprecedented sensitivity, allow clinicians to detect its presence.

The low-cost technology is easy for a clinician or patients themselves to use, is nearly pain-free, and could eliminate the need for a trip to the hospital just for a blood draw. The patches only go about 400 microns deep into the dermal tissue, so they don’t even touch sensory nerves.

The research, from the lab of Srikanth Singamaneni, a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering & Material Sciences, was published online January 22 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

These patches have a host of qualities that can make a real impact on medicine, patient care, and research. They would allow researchers and other healthcare providers to monitor biomarkers over time, which is particularly important when it comes to understanding how immunity plays out in new diseases.

For example, researchers working on COVID-19 vaccines need to know if people are producing the right antibodies and for how long. “Let’s put a patch on,” Singamaneni said, “and let’s see whether the person has antibodies against COVID-19 and at what level.”

For people with chronic conditions or clinical trial participants who require regular monitoring, microneedle patches could eliminate unnecessary trips to the hospital or study site, saving money, time, and discomfort—a lot of discomfort. In the lab, using this technology could also limit the number of animals needed for research, Singamaneni said.

Edited by Gary Cramer