A Q&A with ACRP Diversity Advisory Council member Otis Johnson, PhD, MPA, Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Sustainability Officer at Clario.

As we mark Black History Month, what are your thoughts on overall efforts to improve diversity within the clinical trials ecosystem?

I am encouraged by how focused we are as an industry on addressing the serious underrepresentation of diverse populations in clinical trials.

Although I was quite happy that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a draft guidance last year on improving patient diversity in clinical trials, I saw room for improvement and provided feedback through two industry consortia. I felt that the guidance was not powerful enough. The language was not strong enough to drive the action needed to make clinical trials more diverse. Throughout the draft guidance, there are reminders that these are nonbinding recommendations. In other words, they are optional, and it is OK if you choose not to follow them. There are no consequences and no incentives.

As I was reading the draft guidance, I reflected on my days at Merck designing clinical trials for new therapies for respiratory conditions. We would retrieve the relevant FDA guidance for industry and would follow it exactly. We did this because there was an inherent fear that if we did not follow the guidance, this might ultimately jeopardize the approval of the investigational drug. While reading the draft guidance on how to increase patient diversity in clinical trials, I was hoping to experience that same feeling. Unfortunately, I did not. In other words, the diversity guidance seemed less authoritative than indication guidance.

It seems that the federal government shared this perspective, as the requirement for clinical trial diversity has now become law. It will no longer be optional to submit a diversity plan for Phase III trials – instead, this will now be required. This is a good thing. We must accept that the richest evidence comes from diverse trial participants, and we should not accept that a trial is of good quality if it did not have diverse enrollment.

There are arguments in favor of rejection of marketing applications based on insufficiently diverse studies. Recently, the FDA rejected a China-only study. However, it may take five or more years for this approach to scale. By that time, I believe studies with adequately diverse patient groups will receive priority review from regulators, while those lacking diversity will be sent back to the drawing board, with a requirement for more research, such as post-marketing commitments.

What role does site selection have in improving recruitment of diverse patients?

Site location and staffing are key elements in gaining access to underserved minorities to improve trial diversity – yet some sponsors have been reluctant to include new sites in their studies. In 2021, the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) published findings from a survey of approximately 4,000 clinical research site staff and healthcare practitioners. The survey found a strong association between research site staff diversity and patient diversity. The CSDD noted that staff at sites in urban settings tended to be more diverse, recruited more diverse patients, and usually had infrastructure in place, such as standard operating procedures (SOPs), to engage and enroll diverse patients. Some of these sites may be inexperienced, but it is still worth including them, because they are the gateway to more diverse trials.

One rationale for excluding less experienced sites is the potential risk to data quality – yet we are risking data quality by not running diverse trials. The lack of clinical trial diversity is a much bigger problem than signing up and training research-naïve and less experienced sites that have access to diverse patients.

One barrier to trial participation is that people who live in remote, rural areas tend to be far from academic medical centers and other research sites. A promising approach is being taken by some retail pharmacies, including Walgreens, CVS, and Walmart, bringing research into these communities to break down geographic barriers to clinical trial diversity.

As a member of the ACRP Diversity Advisory Council (DAC), what initiatives are you currently working on?

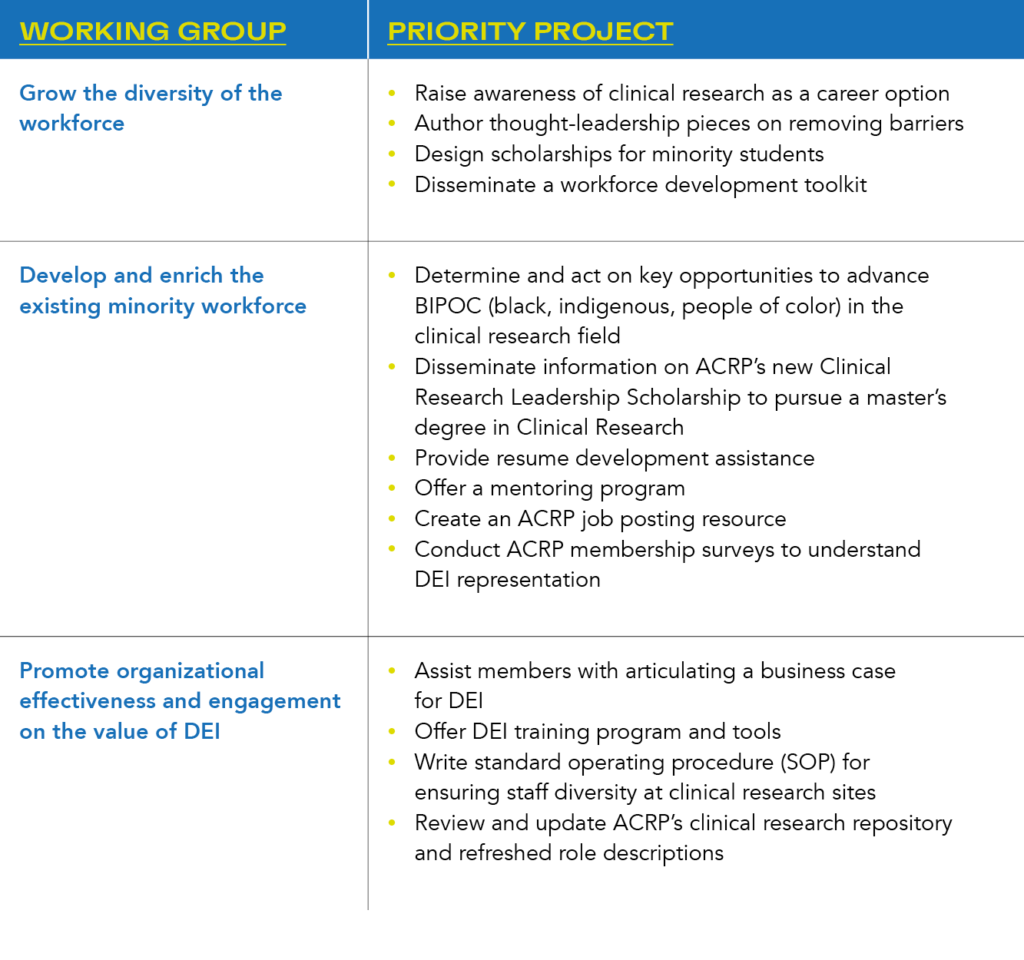

The DAC is a group of industry leaders who serve as a volunteer resource for ACRP as it works toward growing and increasing diversity in the clinical research workforce. We firmly believe that a diverse workforce is part of the solution to the lack of patient diversity in clinical trials. The DAC’s scope is to recommend and help implement strategies to recruit, retain, and advance outstanding, high-quality clinical research professionals and students from historically underrepresented groups. This is a core pillar of the ACRP Workforce Development initiative, which is endorsed by ACRP’s Board of Trustees.

To deliver on this mandate, the DAC is organized into three working groups, each with a set of priority projects:

Could you outline some recent achievements by the ACRP Diversity Advisory Council?

Recent achievements include:

- Publication of a peer-reviewed article on FDA’s Draft Clinical Trials Act to increase clinical trial diversity in the Food and Drug Law Institute magazine, Update (https://www.fdli.org/2023/01/association-of-clinical-research-professionals-response-to-fda-draft-guidance-on-diversity-in-clinical-trials/). In the paper, DAC members and industry collaborators advocated for clinical trial diversity requirements and not only recommendations.

- On the heels of the new U.S. law requiring a diversity plan for every pivotal Phase III clinical trial, I chaired a government listening session on how decentralized research may be used to enhance equitable participation in emergency clinical trials. Employees from several government agencies, including the FDA, Office of Science and Technology Policy, and Office of the National Coordinator, attended the session.

- ACRP produced several short videos of members speaking about how they got into clinical research and why it is an attractive and fulfilling career path. These videos are posted on the ACRP website and have been posted to LinkedIn and other social media platforms.

- Through a collaboration with Black Women in Clinical Research, whose CEO is a part of the DAC, ACRP supported resume improvement workshops for existing and aspiring clinical research professionals.

What steps would you suggest for increasing the diversity of patients recruited for clinical trials?

We all have a role to play in making clinical trials more diverse and inclusive. It starts with study design, which must be built around the patient, keeping them at the heart of the trial. In the past, it was common to copy and paste from existing protocols. Patient input was rarely factored into the protocol design. Today, protocols must be built with input from a diverse group of patients to bolster the scientific and operational rigor of the design.

Last year, I listened to a black physician speak about a trial she was invited to participate in as a primary investigator. The trial protocol assumed that a medication needed by the clinical trial volunteers during the trial would be covered by their health insurance. She was shocked at this assumption and at the naïvety it represented. Her site is in a predominantly minority location, where many individuals have no health insurance. Those with health insurance were mostly underinsured. There was no way she could successfully enroll such a trial – effectively excluding this patient population, along with similar ones at other locations. The protocol design team at that sponsor should have flagged this issue.

Specific steps to improve diversity include:

- Requiring that the diversity of trial participants adequately reflects real-world populations impacted by the disease of interest. Ideally, these populations would be proportionately included at all stages of development.

- Implementing efforts to build trust among underrepresented communities by fully acknowledging past damage and working to resolve biases and improve healthcare access for underserved populations.

- Broadening eligibility criteria for study participants if appropriate – and if this will not affect the scientific integrity of the data – and including research-naïve sites to widen access to diverse populations.

Decentralized clinical trials have increased in popularity during the pandemic. How can these improve access to underserved populations?

Decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) can support a more patient-centered approach by reducing barriers to participation. It is well understood that not everyone has equal access to the basic conveniences of transportation, parking, childcare services, and the ability to take time off work to participate in a clinical trial. So, innovations that allow volunteers to participate in clinical trials from anywhere, whether site based, hybrid, or completely remote will help make clinical trials more inclusive.

At my organization, we developed an innovation to allow more patients to participate in respiratory clinical trials. I spent a lot of time in respiratory drug development and know how important it is to have quality, reproducible spirometry to measure lung function. Expert coaching is the key to obtaining these quality, reproducible spirometry measurements. Until now, this could only be achieved at a traditional site with a live coach. Remote coaching for this technology, with the ability to see the airflow loop “live,” solves this problem. It allows trial participation from anywhere, including from under-represented communities, supporting improved clinical trial diversity.

There have been rapid advances in DCTs during the COVID-19 pandemic, yet sites have often been left out of stakeholder discussions and may be unprepared to manage these models. Sites concerns may center around loss of direct control over elements of the trial, such as oversight of home visits. Sites may also need support to implement new technology, helping to address the fact that they may be under-resourced from workforce and capital perspectives.

DCT technology has the potential to be the great equalizer. However, we should not overlook the power of simple non-technology innovations, such as having diverse teams throughout the clinical trial value chain, including at sponsors, contract research organizations, sites, and clinical trial vendors.

How can clinical research sites best support increased diversity?

Site staff diversity can be improved by outreach to potential clinical researchers within younger populations, including raising awareness of clinical research as a promising career path to students at historically Black colleges and universities, community colleges, and educational institutions. As site workforces develop, efforts to improve diversity should include disability, gender identification, age, sexual orientation, religion, and other elements.

In addition, there is a need to increase the diversity of principal investigators (PIs). Of the total of 8,350 PIs in the U.S., under 10% are Black and few belong to other minorities. Supporting diversity with the PI community is being increasingly recognized as a priority.

Looking ahead, an equitable approach is essential. Site staff should receive specific training on how to appropriately engage with diverse patient populations. Communications should include information about clinical trial opportunities as a care option. It is important not to assume that certain underrepresented groups will refuse to participate in trials; educating and inviting these groups may have a positive impact.

What near-term steps can be taken within organizations to support diversity?

In future, collaboration between all clinical trial stakeholders will be needed to advance diversity in clinical trials. There is scope to raise awareness, understanding and trust among participants in underrepresented populations. All trial stakeholder enterprises should have clear diversity goals, with mandatory training on DEI-related topics.

DCT elements will help engage, recruit, and retain patients from all populations. A hybrid approach is becoming more popular, with some in-person visits and some taking place remotely. This reduces the patient burden, while allowing the study PI to keep oversight of patient safety.

Organizations should put in place a tangible, intentional DEI plan – acknowledging that DEI will not be achieved by chance. A deliberate effort is required, starting with leadership openly committing to improving workforce diversity and inclusion. This should be followed with measurable organizational goals, with staff compensation tied to how well they perform against these goals.

The spotlight on DEI and supporting actions have taken us to a point of no return. DEI will improve. I believe that regulatory agencies will get more involved and be more aggressive in helping to solve clinical trial diversity challenges. Just over a decade ago, we saw dramatic improvements in representation of women in clinical trials. We will see something similar with race and ethnic representation – if we keep up the momentum. All the indicators are that we will do exactly that. It is quite simply impossible to view a trial as being of high quality without adequate representation of all patient populations.