Clinical Researcher—June 2020 (Volume 34, Issue 6)

PEER REVIEWED

Bridget Kesling, MACPR; Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN; Jessica Fritter, MACPR; Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP

Those seeking an initial career in clinical research often ask how they can “get a start” in the field. Some clinical research professionals may not have heard about clinical research careers until they landed that first job. Individuals sometimes report that they have entered the field “accidentally” and were not previously prepared. Those trying to enter the clinical research field lament that it is hard to “get your foot in the door,” even for entry-level jobs and even if you have clinical research education. An understanding of how individuals enter the field can be beneficial to newcomers who are targeting clinical research as a future career path, including those novices who are in an academic program for clinical research professionals.

We designed a survey to solicit information from students and alumni of an online academic clinical research graduate program offered by a large public university. The purpose of the survey was to gain information about how individuals have entered the field of clinical research; to identify facilitators and barriers of entering the field, including advice from seasoned practitioners; and to share the collected data with individuals who wanted to better understand employment prospects in clinical research.

Background

Core competencies established and adopted for clinical research professionals in recent years have informed their training and education curricula and serve as a basis for evaluating and progressing in the major roles associated with the clinical research enterprise.{1,2} Further, entire academic programs have emerged to provide degree options for clinical research,{3,4} and academic research sites are focusing on standardized job descriptions.

For instance, Duke University re-structured its multiple clinical research job descriptions to streamline job titles and progression pathways using a competency-based, tiered approach. This led to advancement pathways and impacted institutional turnover rates in relevant research-related positions.{5,6} Other large clinical research sites or contract research organizations (CROs) have structured their onboarding and training according to clinical research core competencies. Indeed, major professional organizations and U.S. National Institutes of Health initiatives have adopted the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency as the gold standard approach to organizing training and certification.{7,8}

Recent research has revealed that academic medical centers, which employ a large number of clinical research professionals, are suffering from high staff turnover rates in this arena, with issues such as uncertainty of the job, dissatisfaction with training, and unclear professional development and role progression pathways being reported as culprits in this turnover.{9} Further, CROs report a significant shortage of clinical research associate (CRA) personnel.{10} Therefore, addressing factors that would help novices gain initial jobs would address an important workforce gap.

Methods

This mixed-methods survey study was initiated by a student of a clinical research graduate program at a large Midwest university who wanted to know how to find her first job in clinical research. Current students and alumni of the graduate program were invited to participate in an internet-based survey in the fall semester of 2018 via e-mails sent through the program listservs of current and graduated students from the program’s lead faculty. After the initial e-mail, two reminders were sent to prospective participants.

The survey specifically targeted students or alumni who had worked in clinical research. We purposefully avoided those students with no previous clinical research work experience, since they would not be able to discuss their pathway into the field. We collected basic demographic information, student’s enrollment status, information about their first clinical research position (including how it was attained), and narrative information to describe their professional progression in clinical research. Additional information was solicited about professional organization membership and certification, and about the impact of graduate education on the acquisition of clinical research jobs and/or role progression.

The survey was designed so that all data gathered (from both objective responses and open-ended responses) were anonymous. The survey was designed using the internet survey instrument Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. REDCap provides an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources.{11}

Data were exported to Excel files and summary data were used to describe results. Three questions solicited open-ended responses about how individuals learned about clinical research career options, how they obtained their first job, and their advice to novices seeking their first job in clinical research. Qualitative methods were used to identify themes from text responses. The project was submitted to the university’s institutional review board and was classified as exempt from requiring board oversight.

Results

A total of 215 survey invitations were sent out to 90 current students and 125 graduates. Five surveys were returned as undeliverable. A total of 48 surveys (22.9%) were completed. Because the survey was designed to collect information from those who were working or have worked in clinical research, those individuals (n=5) who reported (in the first question) that they had never worked in clinical research were eliminated. After those adjustments, the total number completed surveys was 43 (a 20.5% completion rate).

The median age of the participants was 27 (range 22 to 59). The majority of respondents (89%) reported being currently employed as clinical research professionals and 80% were working in clinical research at the time of graduate program entry. The remaining respondents had worked in clinical research in the past. Collectively, participants’ clinical research experience ranged from less than one to 27 years.

Research assistant (20.9%) and clinical research coordinator (16.3%) were the most common first clinical research roles reported. However, a wide range of job titles were also reported. When comparing entry-level job titles of participants to their current job title, 28 (74%) respondents reported a higher level job title currently, compared to 10 (26%) who still had the same job title.

Twenty-four (65%) respondents were currently working at an academic medical center, with the remaining working with community medical centers or private practices (n=3); site management organizations or CROs (n=2); pharmaceutical or device companies (n=4); or the federal government (n=1).

Three respondents (8%) indicated that their employer used individualized development plans to aid in planning for professional advancement. We also asked if their current employer provided opportunities for professional growth and advancement. Among academic medical center respondents, 16 (67%) indicated in the affirmative. Respondents also affirmed growth opportunities in other employment settings, with the exception of one respondent working in government and one respondent working in a community medical center.

Twenty-five respondents indicated membership to a professional association, and of those, 60% reported being certified by either the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) or the Society of Clinical Research Associates (SoCRA).

Open-Ended Responses

We asked three open-ended questions to gain personal perspectives of respondents about how they chose clinical research as a career, how they entered the field, and their advice for novices entering the profession. Participants typed narrative responses.

“Why did you decide to pursue a career in clinical research?”

This question was asked to find out how individuals made the decision to initially consider clinical research as a career. Only one person in the survey had exposure to clinical research as a career option in high school, and three learned about such career options as college undergraduates. One participant worked in clinical research as a transition to medical school, two as a transition to a doctoral degree program, and two with the desire to move from a bench (basic science) career to a clinical research career.

After college, individuals either happened across clinical research as a career “by accident” or through people they met. Some participants expressed that they found clinical research careers interesting (n=6) and provided an opportunity to contribute to patients or improvements in healthcare (n=7).

“How did you find out about your first job in clinical research?”

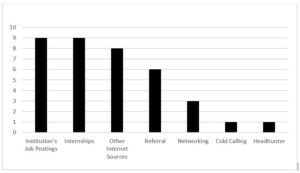

Qualitative responses were solicited to obtain information on how participants found their first jobs in clinical research. The major themes that were revealed are sorted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: How First Jobs in Clinical Research Were Found

Some reported finding their initial job through an institution’s job posting.

“I worked in the hospital in the clinical lab. I heard of the opening after I earned my bachelor’s and applied.”

Others reported finding about their clinical research position through the internet. Several did not know about clinical research roles before exploring a job posting.

“In reviewing jobs online, I noticed my BS degree fit the criteria to apply for a job in clinical research. I knew nothing about the field.”

“My friend recommended I look into jobs with a CRO because I wanted to transition out of a production laboratory.”

“I responded to an ad. I didn’t really know that research could be a profession though. I didn’t know anything about the field, principles, or daily activities.”

Some of the respondents reported moving into a permanent position after a role as an intern.

“My first clinical job came from an internship I did in my undergrad in basic sleep research. I thought I wanted to get into patient therapies, so I was able to transfer to addiction clinical trials from a basic science lab. And the clinical data management I did as an undergrad turned into a job after a few months.”

“I obtained a job directly from my graduate school practicum.”

“My research assistant internship [as an] undergrad provided some patient enrollment and consenting experience and led to a CRO position.”

Networking and referrals were other themes that respondents indicated had a direct impact on them finding initial employment in clinical research.

“I received a job opportunity (notice of an opening) through my e-mail from the graduate program.”

“I was a medical secretary for a physician who did research and he needed a full-time coordinator for a new study.”

“I was recommended by my manager at the time.”

“A friend had a similar position at the time. I was interested in learning more about the clinical research coordinator position.”

“What advice do you have for students and new graduates trying to enter their first role in clinical research?”

We found respondents (n=30) sorted into four distinct categories: 1) a general attitude/approach to job searching, 2) acquisition of knowledge/experience, 3) actions taken to get a position, and 4) personal attributes as a clinical research professional in their first job.

Respondents stressed the importance of flexibility and persistence (general attitude/approach) when seeking jobs. Moreover, 16 respondents stressed the importance of learning as much as they could about clinical research and gaining as much experience as they could in their jobs, encouraging them to ask a lot of questions. They also stressed a broader understanding of the clinical research enterprise, the impact that clinical research professional roles have on study participants and future patients, and the global nature of the enterprise.

“Apply for all research positions that sound interesting to you. Even if you don’t meet all the requirements, still apply.”

“Be persistent and flexible. Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities. This will help develop your own niche within a group/organization while creating opportunities for advancement.”

“Be flexible with salary requirements earlier in your career and push yourself to learn more [about the industry’s] standards [on] a global scale.”

“Be ever ready to adapt and change along with your projects, science, and policy. Never forget the journey the patients are on and that we are here to advance and support it.”

“Learning the big picture, how everything intertwines and works together, will really help you progress in the field.”

In addition to learning as much as one can about roles, skills, and the enterprise as a whole, advice was given to shadow or intern whenever possible—formally or through networking—and to be willing to start with a smaller company or with a lower position. The respondents stressed that novices entering the field will advance in their careers as they continue to gain knowledge and experience, and as they broaden their network of colleagues.

“Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up, regardless [if it is] at clinical trial site or in industry.”

“Getting as much experience as possible is important; and learning about different career paths is important (i.e., not everyone wants or needs to be a coordinator, not everyone goes to graduate school to get a PhD, etc.).”

“(A graduate) program is beneficial as it provides an opportunity to learn the basics that would otherwise accompany a few years of entry-level work experience.”

“Never let an opportunity pass you up. Reach out directly to decision-makers via e-mail or telephone—don’t just rely on a job application website. Be willing to start at the bottom. Absolutely, and I cannot stress this enough, [you should] get experience at the site level, even if it’s just an internship or [as a] volunteer. I honestly feel that you need the site perspective to have success at the CRO or pharma level.”

Several personal behaviors were also stressed by respondents, such as knowing how to set boundaries, understanding how to demonstrate what they know, and ability to advocate for their progression. Themes such as doing a good job, communicating well, being a good team player, and sharing your passion also emerged.

“Be a team player, ask questions, and have a good attitude.”

“Be eager to share your passion and drive. Although you may lack clinical research experience, your knowledge and ambition can impress potential employers.”

“[A] HUGE thing is learning to sell yourself. Many people I work with at my current CRO have such excellent experience, and they are in low-level positions because they didn’t know how to negotiate/advocate for themselves as an employee.”

Discussion

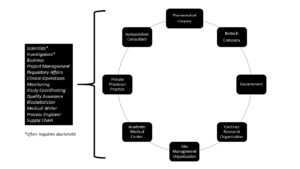

This mixed-methods study used purposeful sampling of students in an academic clinical research program to gain an understanding of how novices to the field find their initial jobs in the clinical research enterprise; how to transition to a clinical research career; and how to find opportunities for career advancement. There are multiple clinical research careers and employers (see Figure 2) available to individuals working in the clinical research enterprise.

Figure 2: Employers and Sample Careers

Despite the need for employees in the broad field of clinical research, finding a pathway to enter the field can be difficult for novices. The lack of knowledge about clinical research as a career option at the high school and college level points to an opportunity for broader inclusion of these careers in high school and undergraduate curricula, or as an option for guidance counselors to be aware of and share with students.

Because most clinical research jobs appear to require previous experience in order to gain entry, novices are often put into a “Catch-22” situation. However, once hired, upward mobility does exist, and was demonstrated in this survey. Mobility in clinical research careers (moving up and general turnover) may occur for a variety of reasons—usually to achieve a higher salary, to benefit from an improved work environment, or to thwart a perceived lack of progression opportunity.{9}

During COVID-19, there may be hiring freezes or furloughs of clinical research staff, but those personnel issues are predicted to be temporary. Burnout has also been reported as an issue among study coordinators, due to research study complexity and workload issues.{12} Moreover, the lack of individualized development planning revealed by our sample may indicate a unique workforce development need across roles of clinical research professionals.

This survey study is limited in that it is a small sample taken specifically from a narrow cohort of individuals who had obtained or were seeking a graduate degree in clinical research at a single institution. The study only surveyed those currently working in or who have a work history in clinical research. Moreover, the majority of respondents were employed at an academic medical center, which may not fully reflect the general population of clinical research professionals.

It was heartening to see the positive advancement in job titles for those individuals who had been employed in clinical research at program entry, compared to when they responded to the survey. However, the sample was too small to draw reliable correlations about job seeking or progression.

Conclusion

Although finding one’s first job in clinical research can be a lengthy and discouraging process, it is important to know that the opportunities are endless. Search in employment sites such as Indeed.com, but also search within job postings for targeted companies or research sites such as biopharmguy.com (see Table 1). Created a LinkedIn account and join groups and make connections. Participants in this study offered sound advice and tips for success in landing a job (see Figure 3).

Table 1: Sample Details from an Indeed.Com Job Search

| Position | Company | Minimum Qualifications |

| Clinical Research Patient Recruiter | PPD | Bachelor’s degree and related experience |

| Clinical Research Assistant | Duke University | Associate degree |

| Clinical Trials Assistant | Guardian Research Network | Bachelor’s degree and knowledge of clinical trials |

| Clinical Trials Coordinator | Advarra Health Analytics | Bachelor’s degree |

| Clinical Research Specialist | Castle Branch | Bachelor’s degree and six months in a similar role |

| Clinical Research Technician | Rose Research Center, LLC | Knowledge of Good Clinical Practice and experience working with patients |

| Clinical Research Lab Coordinator | Coastal Carolina Research Center | One year of phlebotomy experience |

| Project Specialist | WCG | Bachelor’s degree and six months of related experience |

| Data Coder | WCG | Bachelor’s degree or currently enrolled in an undergraduate program |

Note: WCG = WIRB Copernicus Group

Figure 3: Twelve Tips for Finding Your First Job

- Seek out internships and volunteer opportunities

- Network, network, network

- Be flexible and persistent

- Learn as much as possible about clinical research

- Consider a degree in clinical research

- Ask a lot of questions of professionals working in the field

- Apply for all research positions that interest you, even if you think you are not qualified

- Be willing to learn new skills and take on new responsibilities

- Take the best opportunity available to you and work your way up

- Learn to sell yourself

- Sharpen communication (written and oral) and other soft skills

- Create an ePortfolio or LinkedIn account

Being willing to start at the ground level and working upwards was described as a positive approach because moving up does happen, and sometimes quickly. Also, learning soft skills in communication and networking were other suggested strategies. Gaining education in clinical research is one way to begin to acquire knowledge and applied skills and opportunities to network with experienced classmates who are currently working in the field.

Most individuals entering an academic program have found success in obtaining an initial job in clinical research, often before graduation. In fact, the student initiating the survey found a position in a CRO before graduation.

References

- Sonstein S, Seltzer J, Li R, Jones C, Silva H, Daemen E. 2014. Moving from compliance to competency: a harmonized core competency framework for the clinical research professional. Clinical Researcher 28(3):17–23. doi:10.14524/CR-14-00002R1.1. https://acrpnet.org/crjune2014/

- Sonstein S, Brouwer RN, Gluck W, et al. 2018. Leveling the joint task force core competencies for clinical research professionals. Therap Innov Reg Sci.

- Jones CT, Benner J, Jelinek K, et al. 2016. Academic preparation in clinical research: experience from the field. Clinical Researcher 30(6):32–7. doi:10.14524/CR-16-0020. https://acrpnet.org/2016/12/01/academic-preparation-in-clinical-research-experience-from-the-field/

- Jones CT, Gladson B, Butler J. 2015. Academic programs that produce clinical research professionals. DIA Global Forum 7:16–9.

- Brouwer RN, Deeter C, Hannah D, et al. 2017. Using competencies to transform clinical research job classifications. J Res Admin 48:11–25.

- Stroo M, Ashfaw K, Deeter C, et al. 2020. Impact of implementing a competency-based job framework for clinical research professionals on employee turnover. J Clin Transl Sci.

- Calvin-Naylor N, Jones C, Wartak M, et al. 2017. Education and training of clinical and translational study investigators and research coordinators: a competency-based approach. J Clin Transl Sci 1:16–25. doi:10.1017/cts.2016.2

- Development, Implementation and Assessment of Novel Training in Domain-based Competencies (DIAMOND). Center for Leading Innovation and Collaboration (CLIC). 2019. https://clic-ctsa.org/diamond

- Clinical Trials Talent Survey Report. 2018. http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/node/351341/done?sid=15167

- Causey M. 2020. CRO workforce turnover hits new high. ACRP Blog. https://acrpnet.org/2020/01/08/cro-workforce-turnover-hits-new-high/

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–81.

- Gwede CK, Johnson DJ, Roberts C, Cantor AB. 2005. Burnout in clinical research coordinators in the United States. Oncol Nursing Forum 32:1123–30.

A portion of this work was supported by the OSU CCTS, CTSA Grant #UL01TT002733.

Bridget Kesling, MACPR, (Kesling.9@osu.edu) is a Project Management Analyst with IQVIA in Durham, N.C.

Carolynn Jones, DNP, MSPH, RN, FAAN, (Jones.5342@osu.edu) is an Associate Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University College of Nursing, Co-Director of Workforce Development for the university’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, and Director of the university’s Master of Clinical Research program.

Jessica Fritter, MACPR, (Fritter.5@osu.edu) is a Clinical Research Administration Manager at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an Instructor for the Master of Clinical Research program at The Ohio State University.

Marjorie V. Neidecker, PhD, MEng, RN, CCRP, (Neidecker.1@osu.edu) is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Nursing at The Ohio State University Colleges of Nursing and Pharmacy.