Clinical Researcher—August 2020 (Volume 34, Issue 7)

RECRUITMENT & RETENTION

Peter Coë

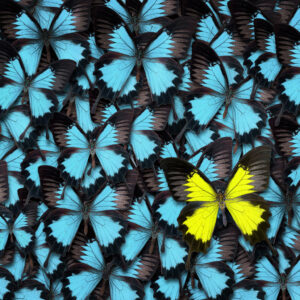

Finding patients with a rare disease to take part in clinical research can be challenging; keeping them engaged in long research programs even more so. These patients, by definition, are few in number, so any one trial site may only have one or two patients per trial to enroll and keep engaged. So how do you treasure those exceptions—those participants who may make the difference between the trial being completed on time or not?

Understanding Rare Disease Patients

Patients with a rare condition often struggle to understand their disease fully. Many will have battled for years to get a diagnosis, and even then be faced with blank faces from healthcare professionals when they ask about alternative treatment options. Research and knowledge around rare diseases, even among specialists, can still be patchy and, as a result, many patients may not have seen anyone who is up to date on the latest knowledge concerning their condition.

Here are some comments shared by members of Raremark’s rare disease communities:

“Having specialists scratching their heads, not knowing anything about the disease you have—it’s quite scary.”

“I had to suffer hours of excruciating pain before I could be taken seriously.”

“The feeling that you’re totally alone, dealing with a rare disease that no one seems to know anything about, is tough.”

We recently asked members of our sickle cell community why they would take part in clinical research. They told us their top motivators were gaining insights into their own health, advancing medical science, and benefiting from the extra medical attention they would receive.

Top 10 Tips on Engaging Patients with Clinical Trials

Based on hundreds of hours of conversations with patients who are interested in joining a clinical trial, here are 10 recommendations on engaging these rare exceptions in research.

- A prompt response is vital to a new patient: within two days of a referral is ideal.

- Please keep the patient’s first appointment, if humanly possible. We have had hard-to-reach patients lose heart and turn their back on research after screening appointments were canceled more than once by study sites.

- Use e-mail to agree on a time for a first phone call with referred patients, and to confirm a screening appointment. Patients often have busy lives outside the clinical trial, and will sometimes be working the same office hours as sites. They may not be instantly available to answer an unexpected call—or, more typically, they are unwilling to answer a call from a number they don’t recognize.

- If new patients prove hard to get hold of, or you want to see medical records before bringing them in for screening and you’re too busy to do the chasing, trial partners may be able help. Tell the trial sponsor you need more support, and be precise about which records you really need to see.

- Appreciate that many patients will be concerned about the effects of coming off an existing treatment, which is often a requirement of joining a trial for an investigational therapy. They may appreciate a conversation about how to mitigate the effects, and some reassurance about all the tests and procedures involved.

- Underline what’s expected of trial participants in the first conversation. People with a rare disease are often highly motivated to take part in clinical research, but may overlook the most obvious requirements—particularly the number and frequency of visits to the study site and the logistics involved in getting there.

- Before enrollment, explain what they can tell their friends and family about the trial. Many people living with a rare disease are used to posting frequently on social media, so they may need guidance on what details they should not post in order to preserve the privacy of their personal health information, the integrity of the trial, and the data being collected.

- Ensure prompt payment of travel expenses and any honoraria. There’s often a concierge service engaged to sort this on the study site’s behalf, but the site coordinator should be familiar with what’s available and how the patient can access it easily.

- While they are on the trial, do share with patients any patient-friendly materials or blogs about living well with their condition. Create opportunities for communicating between study visits.

- Where possible, take the trial to the patient, not the patient to the trial. If study procedures can be done just as well by a study nurse in a visit to the patient’s home, or a video call can replace a site visit, then why not?

All of these tips would be followed routinely in an ideal world, but we appreciate that this often is not an ideal world and that many sites are working with inadequate resources. There are options for help, and it’s worth a conversation with the trial sponsor when it’s needed. Overall, it comes down to treating the patient’s time and commitment with respect.

Communicate well, not only before enrollment, but also while patients are on the trial. (Timely reminders of upcoming appointments are a given.) If a site visit needs rescheduling, it’s really appreciated if it can be done with forethought, not at the last minute. Birthday and seasonal greeting cards are also much appreciated—and a thank you card at the trial’s end for taking part.

Patient Experience and How it Should Influence Trial Design

Having a chronic illness can impact every aspect of a patient’s life, and with a rare disease where specialist support is limited, the magnitude of the impact can feel enormous. Researchers need to understand the everyday reality of living with the disease they are investigating before designing their clinical trial.

For example, some rare diseases lead to patients having to make multiple visits to the hospital, and the idea of taking part in a trial where they also have to visit the trial site frequently could be too much. Our sickle cell community reported visiting the ER about five times a year on average, with some visiting their primary healthcare provider more than 300 times in a 12-month period.

Trial sponsors already invest in travel reimbursement and, occasionally, in making accommodation available for patients near the trial site. Even better for patients with complex needs are more home visits, with nurses going to the patients to perform simple tests and procedures, and even to administer the trial drug.

Patient Experience During Trials

The rise of the internet and social media has brought all kinds of individual patients and those in previously isolated groups closer together. That’s particularly true for people living with a rare disease. They can now find and interact more easily with others affected by the same disease as they share their experiences. If patients have a positive experience during a trial, they are more likely to encourage others they are in contact with to take part in one in future.

When speaking to our sickle cell community, we found members generally had a positive experience with researchers in the trials they had taken part in, but felt the research staff didn’t always answer their questions in ways they could understand.

Taking patients’ needs into account in every aspect of the trial, including the language used and the care provided beyond the immediate demands of the protocol, will ensure better experiences and help to maintain engagement in research.

Encourage Trial Participation Through Understanding the Need

Those responsible for planning rare disease trials need to better understand the world their prospective patients live in. Patient networks can do much to educate their community members about the role clinical trials play in the medical world’s understanding of rare disease, and in the development of new and better treatments; trial sponsors can support these efforts through unrestricted educational grants. However, they can also do a lot more for themselves—through commissioning quality-of-life surveys for example, and by engaging patient panels before the protocol is set in stone—so they better understand the disease, the patient experience, and even what patients really want most from a new treatment.

Peter Coë is Co-founder and Director of Client Services for Raremark. He has 20 years of experience in health communications, with a focus on the development of treatments in areas of unmet medical need, particularly in rare disease. In the last 10 years he has led online campaigns to engage and recruit a wide range of hard-to-reach patient populations for quality-of-life studies and early- to late-stage clinical trials.