Clinical Researcher—January 2021 (Volume 35, Issue 1)

PEER REVIEWED

Mary Costello

Change is never easy, and this past year has presented the world with some seemingly insurmountable challenges—certainly among the biggest faced by any generation living today. As an industry rooted in continuous learning and experimentation with a mission to find new solutions, the clinical research enterprise continues to struggle with how to uphold that mission in a world that needs to limit in-person interactions. The very nature of the work has traditionally demanded the kind of in-person contact that now needs to be limited.

As the COVID-19 virus reached pandemic levels in early 2020, educational institutions around the world were upended almost overnight. Schools and universities closed, and educators had to redesign entire methodologies in ways that suited very diverse populations. Likewise, most clinical trials came to a screeching halt. Clinical trials stakeholders quickly realized that this was more than a brief setback; not only did they need to formulate a strategy for the continuation of research through virtual and hybrid studies, but the onus of developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19 rested squarely on their shoulders.

The re-engineering of education continues to evolve as the pandemic lingers, but clinical research can benefit from what educators have already accomplished. What follows are five key lessons learned from educators and students, translated to the clinical research environment for consideration when developing training and trial conduct strategies going forward.

Change Management—Start Where the Patient Is

The traditional urge for a strong educational focus on study components when training clinical researchers has been compounded by the need to upskill staff and patients in technology. Significant changes such as a wholesale switch to decentralized trials require a sturdy foundation. Short-circuiting the thoughts, feelings, and downstream effects of everyone involved will not result in a successful transition. It is vital for both trainers and their “students” to acknowledge the potential for confusion, fear, and learning curve difficulties to be experienced by research team members and patients faced with learning about and using new trial-related technologies and procedures.

According to J. A. Miller, PhD, “Being open to the current crisis-driven educational opportunity is a call to action. The reputation and integrity of your institution—and you!—depends upon your offering engaging online classes.”{1} The same holds true for clinical research, as the need to embrace virtual and hybrid trials is not temporary.

Staff, patients, and physicians all have concerns and questions that are unique to their roles. Beyond that, issues such as comfort with, and access to, internet services and smartphones vary by age, culture, and other socioeconomic factors. Beyond devices and internet speed, multiple platforms, logins, and lack of integration further complicate the learning curve. For research processes, study teams and patients are experiencing these same challenges. Utilizing a decentralized trial platform with a single sign-on for all research tasks will mitigate such challenges for all stakeholders.

The next step is to develop a thorough formative assessment to understand how well participants are engaging with the new technologies and procedures inherent in virtual and hybrid trials. This will guide further process design and resource allocations.{2} DePaul University Associate Professor of Political Science Molly Andolina, PhD, explains that a roadmap of transition for a program from in-person to hybrid or remote is imperative. Both staff and patients should have checklists. She says, “Turning on a dime, as we had to do [at DePaul in early 2020], just did not work well.”

The plan for general implementation should include a thorough training process for staff and patients. Training vehicles should comprise a mix of written documents, live web meetings, interactive online modules, and short videos. Ideally, videos for younger users should last two minutes, as their attention span drops off significantly after that.{3}

To address the mental and emotional factors, consider incorporating a role play for staff that reflects the new day-to-day workflow. To build empathy for the patient experience, staff should also participate in role play of patients, particularly since they will be a source of tech support for patients. Establishing a “super user” at each site will help alleviate fears of what might go wrong and who will provide support.

Further, it is essential that training goes beyond features and functions to incorporate the “whys” for staff and patients. With any new process, understanding the why and how each person benefits helps to ensure success. When creating messaging to staff and patients about the new options, reinforce that they represent opportunities to ease burdens and improve workflows for everyone. The message should address security and privacy of information and reflect patients’ cultural sensitivities. For example, in some countries, patients will not want private health information, such as images of a medication, stored on their mobile device. Communicate with study teams, investigators, and patients that there will be options for how to participate in a study.

“I think that too often the focus is on what’s lost and not on what’s potentially gained” regarding remote instruction, said Chris Dede, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education who has studied the use of educational technology in schools.{4} If we take this perspective when considering virtual and hybrid trials, adoption will be easier.

Process Design—The End is the Beginning

Consider the desired outcomes for the proposed research team and/or patient training and technology usages first, then back into the process design. Strip down expectations to be sure each step is truly necessary to achieve the outcome. Like lean methodology, if a component does not have value, it has no place in the value chain. The influence of site perspective on trial design is also imperative.

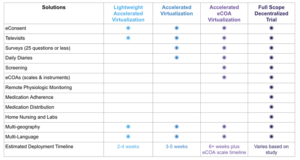

Carefully evaluate which components of each study can be conducted virtually. For example, with remote monitoring devices, sites can accurately collect vitals such as weight and blood pressure without an in-person visit. Structures need to be in place for responding to data collected through the technology, and this may require new decision support processes. Map out the best options, including those that are already part of the infrastructure. An example of a progressive implementation of virtual solutions is illustrated below.

Remote and hybrid learning have created the potential for new teaching models. Some schools have enlisted specific virtual learning teams to develop and provide virtual instruction for remote students, while continuing to utilize existing teachers for classrooms with students attending in-person. For remote instruction, “learning navigators” can be leveraged to help students, teachers, and families use technology effectively.{5} The lesson is to use this opportunity during process redesign to evaluate staffing patterns and optimize the skill sets within the research team.

Once processes are redesigned, update operating procedures, job descriptions, and performance criteria to reflect technology proficiency and new workflows. Additionally, many sites have found that virtual and hybrid trials offer flexibility for staff to work remotely on occasion, particularly when kids are at home participating in distance learning. Designing standards that align with security and privacy regulations may seem daunting, but many have found that the added flexibility helps retain valuable team members.

As the clinical research enterprise moves forward with new processes and uses of technology, feedback must guide its progress. Using short surveys, input can be gathered from patients and staff at regular intervals; more importantly, responses to their feedback with meaningful changes will continue the cycle of improvement.

Contingency Plans—Preparation is Half the Battle

With any new process or technology, there will be hurdles, so it is important to create contingency plans for staff and patients; if they are prepared for the occasional glitch, they are less likely to experience distress when it occurs, and therefore more likely to stay engaged. Keeping FAQs updated and making short videos available on how to handle common issues like pop-up blockers, browser type differences, and time-out errors greatly reduce time that staff spend providing tech support.{1} Troubleshooting tips can be created in partnership with the site’s information technology group or technology vendor and customized by staff through training and role play exercises.

Creativity and Flexibility—One Size Does Not Fit All

Both education and research are rooted in methodical rigor. Study teams and research participants are conditioned—rewarded even—for rigor. However, the need for creativity and flexibility must be recognized. Factors that contribute to differentiated needs in online environments include technical skills, site capabilities, participant disabilities, economic hardships, or unstable home environments.{5}

“Remote education can’t be a simple replication of the in-person classroom interaction,” says Professor Andolina, and the same is true of clinical research. Patients need the ability to choose which elements of a clinical trial they wish to do remotely and which they prefer to do in person. Since one size does not fit all, flexibility of modules is important; for virtual and hybrid trials to be effective and efficient for patients and physicians, options must be available.

It starts with trial design. Historically, scientific rigor guided the creation of protocols without flexibility in mind—and for good reason. However, the clinical research enterprise must innovate to ensure it can meet the needs of participants, and virtual or hybrid trials offer the opportunity for real-world evidence like never before. Clinical trials teams can maintain vigilance to scientific rigor while also ensuring there are valid and reliable options that suit multiple participants’ needs.

The Human Element is the Key to Survival

It is unclear how long various restrictions and lockdowns will last, and the long-term ramifications of the pandemic on the world remain unknown. Study teams and research participants are accustomed to in-person interactions. Loss of interpersonal contact accompanied by the mental stress of losing touch with family and friends, job loss, virus fears, and continued health issues may become overwhelming for even the strongest people.

It is important to underscore that technology is just the means to an end. Like education, the relationship between patient and physician is also key, and this relationship can be enhanced in a virtual world by providing modular options. Approaching the transition in a holistic way, including mental health, is of paramount importance.

“People want to feel listened to. Aside from devices or internet service, we need to make a concerted effort from the very beginning to understand influences the pandemic has had on them and their families,” encourages Professor Andolina.

Clinical research can leverage televisits to maintain face-to-face interaction and the ability to read emotions such as sadness or physical symptoms like fatigue. As live video is used to maintain relationships with colleagues, family, and friends, comfort levels with digital interaction in the healthcare space will grow. Additionally, as patients transition more of their ongoing healthcare management to virtual care, their expectations about virtual options for research participation will continue to grow.

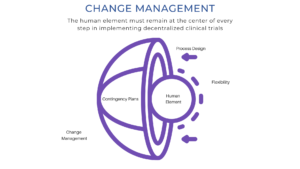

It is clear that the access, skills, process, socioeconomic, cultural, and mental health challenges of the remote education transition mirror those of clinical research. If these lessons from the classroom are applied to keeping the human element at the center (as illustrated below), research teams can make the transition more successfully and be ready for the next hurdle because, in the words of Heraclitus, “Change is the only constant.”

References

- Miller JA. 2020. Eight Steps for a Smoother Transition to Online Teaching. Faculty Focus. See full resource here.

- Aremelino T. 2020. As Schools Go to Distance Learning, Key Strategies to Prevent Learning Loss. See full resource here.

- Fishman E. 2016. How Long Should Your Next Video Be? See full resource here.

- Lieberman M. 2020. Covid-19 and Remote Learning: How to Make it Work. Education Week. See full resource here.

- Dorn E, Panier F, Probst N, Sarakatsannis J. 2020. Back to School: A Framework for Remote and Hybrid Learning Amid COVID-19. McKinsey & Company. See full resource here.

Mary Costello is Head of Site and Trial Network for Medable in Austin, Texas.