Clinical Researcher—June 2022 (Volume 36, Issue 3)

PEER REVIEWED

Deanna M. Golden-Kreutz, PhD; Angela O. Sow, MACPR; Michelle R. Bright, MA; Brad H. Rovin, MD

For more than two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected every sector of the global economy, including the clinical and translational research enterprise.{1} Academic medical centers (AMCs) have faced the challenges of an apprehensive health system concerned with maintaining patient and healthcare worker safety with an emergent call to advance COVID-19 knowledge through research.{2} Even as AMCs implemented investigational approaches and treatments, the pandemic exposed the need for new and broader strategies in order to successfully operationalize and manage research as both an urgent and now clearly a long-term response.{1,3} However, a review of the pandemic’s impacts on the larger clinical research landscape is needed to fully understand the environment in which newer research processes have been and continue to be implemented.

Importantly, this article illustrates the wide-ranging impact of COVID-19 on research processes and associated best practices that have emerged to manage these impacts on the research environment at The Ohio State University Medical Center. Four overarching key strategies are highlighted: 1) leveraging existing research management infrastructure; 2) establishing a COVID-19 research policy; 3) developing multidisciplinary research working groups; and 4) strengthening connections among institutional research stakeholders. These strategies demonstrated success in the initial response to the pandemic and have remained critical for research management throughout the ongoing pandemic.

Leverage Research Management Infrastructure

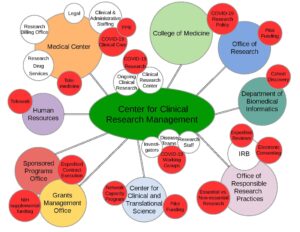

The pandemic has permeated academic and administrative operations. Figure 1 illustrates the impact of COVID-19 on research processes at the institutional level as unprecedented shifts in routine clinical practices continue to be reflected in updated and ever-changing federal, state, and local university guidelines for research.

Figure 1: COVID-19’s Impact on the Research Landscape

The literature to date has discussed how some AMCs mobilized their research response through the creation of a COVID-19 oversight group located within their College of Medicine, Office of Research, Clinical Translational Science Award Center, or some combination of these institutional entities.{4} Our AMC leveraged a centralized administrative infrastructure for managing non-cancer human subjects research, the Center for Clinical Research Management (CCRM), to rapidly oversee and implement COVID-19 research. The CCRM, supported through The Ohio State University’s College of Medicine, strategically aligns resources and research personnel with the needs of investigators and disease-specific research teams.

The connectivity of the research infrastructure with the larger landscape and multiple stakeholders is demonstrated in Figure 1. The red circles highlight the pandemic-related impacts and/or adjustments that have been necessary to successfully implement and maintain overall research activity. As such, the infrastructure of the CCRM has rapidly addressed the continuously evolving direction of COVID-19 research, offering an organized pathway for conducting research while also managing these efforts with ongoing regulatory, fiscal, operational, and personnel oversight.

The size of the CCRM (1,600 studies with 250 principal investigators and 219 research staff across 22 departments, centers, and institutes) has provided the ability to disseminate information quickly and broadly. At the pandemic’s onset, COVID-19 research was prioritized while other ongoing and new non-COVID-19 studies were temporarily halted. Importantly, the CCRM’s infrastructure fostered movement out of individual research silos into collaborative research groups, as well as connected multiple stakeholders who brought several types of expertise together to address the research questions generated by the pandemic.

The utilization of existing centralized research infrastructure has offset challenges that would have been inherent to decentralization of activities, including effort redundancy, miscommunication, and lack of cohesive research strategy. The centralized oversight has also allowed for ease in administration as over time non-COVID-19 research, placed on hold at many AMCs, has largely restarted and continues amid the ongoing pandemic.

Establish COVID-19 Research Policy

The pandemic response has been unprecedented with investigators from all areas of medicine, not simply virology and infectious disease, designing projects to understand, treat, and prevent COVID-19.{5} Many investigators initially lacked experience in conducting research in an environment where the patients, staff, and scientists are at risk through even the simplest of in-person interactions, where biospecimens present significant and often unknown risks, and where personal protective equipment (PPE) has been in short supply and, at times, appropriated by the clinical mission.

In response to managing these risks, a comprehensive research policy was implemented through the College of Medicine, with oversight by the CCRM, to identify and guide investigators seeking to engage in COVID-19 research. This policy has required investigators to complete an impact and planning assessment for any COVID-19 research (e.g., laboratory-based, biorepository, observational, interventional, and therapeutic). The assessment includes those factors identified as most important by research and medical leaders as to whether to engage in a proposed research study: impact on healthcare and research team safety, PPE resources needed, ability to implement regulatory and biosafety safeguards, scientific merit, and funding status.

In practice, assessment approval has been required prior to seeking institutional review board (IRB) approval for COVID-19 studies or modification of existing studies adding COVID-19-related aims. Figure 2 illustrates the strategy for managing COVID-19 research. The policy with its associated review process has been successful in the identification, tracking, and management of our AMC’s COVID-19 research response (215 assessments received; 145 approved to move forward, e.g., IRB submission as applicable).

Figure 2: Strategy for Implementation and Management of COVID-19 Research

Create Multidisciplinary Research Working Groups

In response to the pandemic and the call for clinical research, four multidisciplinary coronavirus-centric working groups (e.g., inpatient/intensive care, outpatient, biorepository, and healthcare workers) were created and have served as another means of organizing the research response. These working groups consisting of investigators and clinical research personnel from differing disciplines, have been responsible for driving study feasibility (reviewing 90 proposals and opening 43 studies to date), making final recommendations for study selection and prioritization, and reporting progress and associated obstacles to the centralized research leadership (CCRM).

Study selection and prioritization was based on those studies deemed as contributing data to the larger understanding and treatment of the COVID-19 virus and were consistent with investigator interest/knowledge, patient availability for enrollment, and resources (e.g., personnel, equipment). The working groups have also helped with early identification of ineffective investigational therapies enabling prompt operational pivots to subsequent studies in the queue.

Additionally, studies are grouped and prioritized by intervention type to limit those with overlapping mechanisms of action. Study categorization has improved selection efficiency and allowed for the development of a diverse portfolio of COVID-19 studies that improve patient care by providing treatment options. Whenever possible, research protocol requirements have been aligned to standard of care/daily care practices to manage added work for practitioners.

The working group model, further illustrated in Figure 2, has provided a structure that fosters consensus building across disciplines in the selection and implementation of studies that show the most promise for treating patients, as well as contributing to scientific knowledge (the two highest priorities for study selection). Currently, these working groups have remained in place to continue guiding study selection and prioritization regarding treatments and the long-term impacts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Connect Institutional Research Stakeholders

Increased institutional connectivity and regular review and interpretation of COVID-19 guidelines have been conducted communally amongst Ohio State research stakeholders (e.g., CCRM, Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS), disease-based research units, IRBs, sponsored programs, compliance offices) to ensure clarity and ease of implementation.{6} Throughout the pandemic, guidelines reviewed have included definitions of essential versus non-essential research, cessation of in-person research visits, increased use of telemedicine, transition to telework, and utilization of touchless consenting practices.

For those investigators and research staff involved in consenting COVID-19 patients into studies, a weekly call was initially established to review updates to guidelines and research processes specifically related to e-consenting, documentation, and screening. This has helped to establish common practices and maintain regulatory compliance standards (see Table 1 for a summary of workflow adjustments and policy changes that have been related to COVID-19). These research-related adjustments remain pertinent to ongoing research operations as the pandemic continues and COVID-19 studies have largely transitioned from emergency use studies to randomized clinical trials and, more recently, into long-term outcome studies.{7}

Table 1: Clinical Research Workflow Adjustments and Policy Changes Related to COVID-19

| PERSONNEL | CONSENT PROCESS | RESEARCH CONDUCT | RESEARCH DESIGN |

| Use of PPE (limit use to essential and/or COVID-19 research) | Submission of remote/distance consent discussion processes with initial IRB applications | Utilization of telemedicine for study visits | Alignment of study procedures with standard of care to limit staff exposure |

| Transition to telework (ensure staff had compliant and adequate technology) | Application of eSignature platforms for obtaining subject/Legally Authorized Representative signatures | Utilization of home healthcare to obtain key safety data (labs, ECG, etc.) | Execution of adaptive protocol design |

| Formation of interdisciplinary teams of coordinators | Utilization of electronic communication platform for facilitating consent process (discussion and signatures) | Increased use of remote monitoring of data | Engagement with IRB to include vulnerable populations (prisoners, pregnant women) |

| Implementation of weekly virtual meetings with COVID-19 research staff to improve efficiency and recruitment | Application of eSignature platforms for obtaining regulatory document signatures | ||

| Enhancement of remote investigational product distribution |

Additionally, communication between the centralized research infrastructure (CCRM) and the CCTS has contributed to the alignment of institutional COVID-19 research priorities with national initiatives to combat the pandemic. The Network Capacity Program of the CCTS has identified opportunities to participate in COVID-19 clinical and translational research studies supported through national and regional collaborative networks. This communication has allowed the CCRM to engage in prompt dissemination of interest to the appropriate investigator(s) and their respective disease teams as they are readily identifiable. This, in turn, has allowed for timely responses to research inquiries and site questionnaires, and for timely initiation of study startup activities.

The overall benefit of connectivity to stakeholders has been even more clearly manifested throughout the pandemic, as our evolving understanding of the nature of the virus and the associated guidances have significant consequences for all members of the clinical and scientific community. Swift implementation of large-scale COVID-19 practices has required numerous successive and parallel operations on every level of the AMC, thereby showcasing collaboration and institutional connectivity.

Conclusions

Along with illustrating the pandemic’s initial and ongoing impacts on the AMC research landscape at The Ohio State University Medical Center, this article has highlighted best practices for navigating these impacts. The key strategies of utilizing and extending existing research infrastructure, establishing common policies, implementing identifiable leadership through multidisciplinary working groups, and driving increased connectivity and consensus building among stakeholders has placed this AMC in the best position possible to handle the challenges as the pandemic initially developed, worsened, and now continues to evolve into waxing and waning episodes.

These best practices, born out of necessity, highlight how quickly effective research management changes can be created and implemented and serve as a guidance for other AMCs as well as other groups engaged in clinical research. Importantly, the processes successfully mobilized to ensure adaptability and consistency in clinical research operations have remained in place throughout the ongoing pandemic in order to continue effective and responsive clinical research management.

The lasting impact of COVID-19 on research-specific processes (e.g., use of eConsent, offsite monitoring) will also continue to evolve along with the pandemic, as the need for advancements in research will coexist with the need for effective clinical management of the COVID-19 illness.

Acknowledgement

Salary support for Deanna M. Golden-Kreutz, Angela O. Sow, and Brad H. Rovin was provided in part by National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR002733. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

References

- Woolliscroft JO. 2020. Innovation in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 95(8):1140–2. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/fulltext/2020/08000/innovation_in_response_to_the_covid_19_pandemic.23.aspx

- Pulley JM, Jerome RN, Rice TW, et al. 2020. Equipoise and research in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 5(1). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-clinical-and-translational-science/article/equipoise-and-research-in-the-current-covid19-pandemic/B1CB9D371FCE6ACEE5C0FB3762D0724E

- Araujo DV, Watson GA, Siu LL. 2020. The Day After COVID-19—Time to Rethink Oncology Clinical Research. JAMA Oncol. 7(1): 23–4. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2769924

- Gravelin M, Wright J, Holbein MEB, et al. 2021. Role of CTSA institutes and academic medical centers in facilitating preapproval access to investigational agents and devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 5(1):e94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8134898/

- McCormack WT, Bredella MA, Ingbar DH, et al. 2020. Immediate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on CTSA TL1 and KL2 Training and Career Development. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 4(6):556–61. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-clinical-and-translational-science/article/immediate-impact-of-the-covid19-pandemic-on-ctsa-tl1-and-kl2-training-and-career-development/35E639277CE2803BC9A5914D84BD4AB5

- Gulick RM, Sobieszczyk ME, Landry DW, et al. 2020. Prioritizing clinical research studies during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from New York City. Journal of Clinical Investigation 130(9):4522–4. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/142151

- Nabhan C, Choueiri TK, Mato AR. 2020. Rethinking Clinical Trials Reform During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Oncol 6(9):1327–9. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2769129

Deanna M. Golden-Kreutz, PhD, (Deanna.golden-kreutz@osumc.edu) is Senior Director of the Center for Clinical Research Management in the College of Medicine and Program Director for Participant & Clinical Interactions in the Center for Clinical and Translational Science at The Ohio State University.

Angela O. Sow, MACPR, (sow.21@osu.edu) is an Instructor for the Masters of Clinical Research Program in the College of Nursing and a former Clinical Research Manager for the Participant and Clinical Interactions and Network Capacity Programs in the Center for Clinical and Translational Science at The Ohio State University.

Michelle R. Bright, MA, (Michelle.bright@osumc.edu) is Director of Protocol, Personnel, and OnCore Management for the Center for Clinical Research Management in the College of Medicine at The Ohio State University.

Brad H. Rovin, MD, (Brad.rovin@osumc.edu) is Medical Director of the Center for Clinical Research Management and Division Director of Nephrology for the Department of Internal Medicine in the College of Medicine at The Ohio State University.