Clinical Researcher—April 2024 (Volume 38, Issue 2)

PEER REVIEWED

Justin Scott Brathwaite, BA, PMP, CCRP; Daniel Goldstein, MSN, RN, CCRP; Erin Dowgiallo, BS; Lindsey Haroun, BS; Karah Ashley Hogue, BS; Tracy Arakaki, PhD, PMP, PBA

Clinical trial enrollment of representative populations is critical to the successful completion of a trial. Key to this is ensuring that traditionally underrepresented populations are included. According to Cornell Law School, “[t]he term ‘underrepresented population’ means a population that is typically underrepresented in service provision, and includes populations such as persons who have low-incidence disabilities, persons who are minorities, poor persons, persons with limited English proficiency, older individuals, or persons from rural areas.”{1} Throughout this examination, we identify common barriers that prevent underrepresented patients from enrolling in clinical trials and offer practical solutions, focusing on both future suggestions and evidence-based success stories.

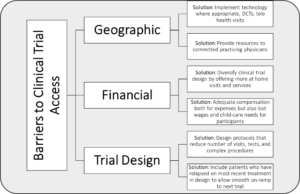

Barriers such as the sparsity of clinical trial sites in rural and underserved communities, inadequate patient reimbursement, and stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria hinder the enrollment of patients from diverse and underrepresented populations (see Figure 1). The strategies we outline are not a comprehensive solution to all issues facing diversity enrollment, but we intend to stimulate conversation within our industry to ensure these barriers are addressed during the design and implementation of clinical trials. Lastly, we will also draw upon our collective firsthand experiences managing a variety of trials of distinct phases and complexities, where relevant, to support our claims.

Figure 1: Common Barriers to Equitable Clinical Trial Access and Potential Solutions

DCTs = decentralized clinical trials

Geographic Limitations

Seidler et al. found geographic proximity is a barrier preventing equitable access to clinical trials. They analyzed ZIP Codes of 174,503 research sites from 2002 to 2007 and discovered most sites are concentrated in urban areas with academic research institutions, large hospital networks, and other established social services; conversely, rural areas had few, if any research sites.{2}

From our experience, even sites in urban areas face recruitment challenges. In general, patients, especially those in underrepresented backgrounds, refrain from traveling long distances to sites. For example, sites in Cincinnati informed us that recruitment was challenging because few patients wanted to travel to the site from the suburbs.

In response, decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) have helped address geographical barriers by extending the reach of novel therapies to rural and underrepresented populations and increasing trial patient diversity. For instance, Sedhai et al. conducted a large, decentralized, randomized controlled COVID-19 trial at a rural satellite hospital in which patient visits were conducted by telehealth and videoconferencing.{3} The trial was successful and enrolled many diverse participants, of which 62.5% were Black and 37.5% female.

In our trials, we noticed underrepresented patients do not always benefit from DCTs because they lack internet connection, and found that providing these patients with Wi-Fi hotspots, ports, and/or computers was a viable solution. Further, implementing technology into clinical trial design has allowed existing rural hospitals to expand their patient reach, but rural areas lack adequate research infrastructure and committed practicing physicians. Addressing this barrier requires cooperation from numerous stakeholders, including government officials, the medical establishment, and the clinical research industry.

Scholars contend that the industry must incentivize physicians to conduct clinical research in rural areas. Woodcock et al. assert that both industry and the medical establishment must provide community-based clinicians in rural areas with the resources, mentorship, and training necessary to run successful clinical trials. These physicians serve local populations and maintain strong rapport with their patients, which are factors critical for enrollment and retention.{4} Moreover, an Elsevier survey revealed that 72% of patients are more likely to participate in a trial that their physician recommends.{5}

Legislators in certain states have recently passed bills increasing the number of physicians in rural areas. A 2023 Texas law allocated resources to rural hospitals incentivizing them to train physicians committed to practicing medicine in rural and underserved areas, but results have yet to be seen.{6} Regardless, more rural physicians present opportunities for the clinical research industry to establish partnerships with these medical providers, introduce them to clinical research, and extend needed clinical care to vulnerable populations.

Financial Issues

Patients find clinical trials appealing because they may receive compensation for their participation, but compensation alone does not imply equitable remuneration. For instance, trial compensation may be insufficient to justify the obligations and burdens patients accrue while enrolled in a study.

Patient liabilities may include time spent away from income-generating activities, along with travel costs to and from the research site. Patients informed us of their inability to attend study visits that conflicted with their work schedules, and that, over time, study participation became more difficult. They also indicated an absence of childcare services was another factor that either prevented them from enrolling in the study or led to them dropping out of it.

Most importantly, Bierer et al. showed that patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds incur significant wage losses when participating in a trial.{7} Therefore, underprivileged and/or underrepresented patients often cannot afford trial participation costs, which may compel them to either prematurely leave the study or not participate. Moreover, drug sponsors underpay participants or simply provide no compensation at all, which limits the inclusion of diverse and underrepresented populations. Hence, these groups are understudied and less likely to receive the benefits of novel therapies.{8}

To address this, we believe patients should be offered at-home services as an option, not a requirement, and this is because while many patients preferred in-home services, many of our trial patients openly declined them. The evidence justifies the inclusion of at-home services in a trial’s design where appropriate, but also aligns with our conservative view. For example, a CenterWatch survey found half (51%) of 1,129 respondents preferred home services.{9} Such visits are beneficial since a nurse can draw blood samples, take vitals, and perform other assessments. We realize the impracticality of having every assessment done at home, but patients can nevertheless benefit from shorter wait times and fewer clinic visits, which could help underrepresented patients increase their income-generating activities.

Nipp, Hong, and Paskett outline how patients participating in U.S.-based trials experience financial difficulty stemming from fees not covered by insurance or study reimbursement.{10} Trials often reimburse patients for travel expenses and pay for any necessary procedures outside the standard of care criteria. However, this does not consider that many procedures considered standard of care may not be fully reimbursed by a patient’s insurance or Medicare coverage. As a result, a patient who would have normally needed a single blood draw each month at an out-of-pocket cost of $10 for a standard treatment regimen may now have to pay for multiple $10 draws per month.

These out-of-pocket costs can financially devastate underrepresented patients, especially if they lack insurance. To address this barrier, we recommend that the industry works with legislators to establish a clinical trial insurance program aimed at low-income patients, to minimize unexpected costs and expand access.

Clinical Trial Design and Awareness

Another barrier we witnessed is an overly complex and burdensome schedule of assessments requiring multiple visits outside treatment days. For example, we managed a kidney trial with a pharmacokinetic sub-study mandating urine draws every 12 hours. Although nurses and study coordinators informed us that many protocols were impractical, their feedback was never considered. This is a mistake because these health professionals can provide valuable insight into designing less burdensome and more feasible protocols. We contend that protocols should be patient-centric and include insight from numerous stakeholders, not just scientists and board members. Thus, protocols should enable sponsors to obtain the minimum scientific data necessary to establish an accurate safety profile and efficacy.

Our industry must address how clinical trial protocols are designed, which can exclude patients from specific populations. All clinical trials contain baseline criteria that patients must satisfy, commonly referred to as eligibility criteria. These criteria can help the sponsor ensure that patients with the appropriate diagnosis are enrolled, but a criterion too stringent can restrict trial enrollment for underrepresented patient populations. According to Sae-Hau et al., one barrier is patients being more likely to enroll if they had relapsed on their most recent treatment, as opposed to those patients who were undergoing current therapy, or in a maintenance period.{11} This is an opportunity for our industry to engage sites early in the process by reviewing the protocol prior to patient enrollment. Physicians and site staff can present their opinions if the criterion is too stringent and consider patients who meet most of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which will also present a streamlined enrollment approach to expedite initiation into the trial.

Desai et al. showed that clinical trial patient recruitment is undoubtedly a major challenge for the industry, as 80% of clinical trials fail to meet initial enrollment timelines.{12} Likewise, clinical trials are in dire need of effective marketing and advertising strategies to bolster awareness among various patient populations.{13} Some traditional recruitment methods include media campaigns, advertisements, and physician referrals; online recruitment methods may include social media ads and search engine advertisements, which can allow research teams to target more specific and nuanced patient populations.

Brøgger-Mikkelsen et al. conducted a meta-analysis which found that studies utilizing online recruitment methods recruited patients much more quickly than traditional methods and were more cost effective.{14} Conversely, traditional methods fared much better when it came to enrolling screened participants into the trial. Taken together, the findings suggest that study teams should consider using online recruitment methods to target patients, and then scheduling in person visits to assess those patients.

However, recruitment challenges also stem from the community’s lack of awareness of clinical trials. One study found that, among a representative sample of 3,772 U.S. adults, 41.3% had no knowledge of clinical trials.{15} Addressing the public’s lack of awareness in clinical trials poses challenges, but it is a necessity that the government, industry, and academia should collaborate to address. A starting point would be greater promotion and awareness of ClinicalTrials.gov as a free online resource, as the site contains information on clinical trials across the globe, including their requirements and locations.

A final key consideration is that, if we recognize the difficulties above, including low potential for enrollment at rural clinics, financial circumstances, and unnecessarily limiting trial design, there is still potential for improved awareness of existing clinical trials to which rural clinic providers may refer their patients. There remain massive hurdles for many patients to travel to large urban centers that carry most clinical trials, but this is still an option. To accomplish this, we need to improve outreach to rural clinics to ensure that patients are at least being made aware of potential options. This, coupled with travel reimbursement plans where the guidance is laid out explicitly for patient referrals, would help to alleviate some of the burden to help patients reach critical and potentially life-saving trials.

Conclusion

If the clinical research industry is to ensure that lifesaving therapies have greater efficacy and safety, industry leaders must address the barriers preventing individuals from diverse, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and/or rural backgrounds from participating in trials. We have discussed three barriers to accessing clinical trials for underrepresented patient populations—sparsity of clinical trial sites in rural and underserved communities, inadequate patient reimbursement, and stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria—which all hinder the enrollment of patients from diverse and underrepresented populations (Figure 1). We outlined the necessary initiatives to combat these barriers, starting with industry leaders engaging with rural physicians and providing them the resources and support to conduct trials in under deserved areas.

Additionally, the clinical trial protocol design itself could be diversified to include telehealth visits and traditional onsite visits, where appropriate, to capture the widest range of patients. Moreover, the industry must design protocols with fewer restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria and minimize the number of tests and/or patient visits. Lastly, we considered reducing the travel- and economic-related burdens on patients by offering more home visits and services. This is a necessity given that patients from low-income backgrounds cannot afford to cease working for extended periods.

References

- “Underrepresented Populations” definition. Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu/definitions/uscode.php?width=840&height=800&iframe=true&def_id=29-USC-539800546-1812891535&term_occur=999&term_src=title:29:chapter:31:section:3002#:~:text=The%20term%20%E2%80%9Cunderrepresented%20population%E2%80%9D%20means,individuals%2C%20or%20persons%20from%20rural

- Seidler EM, Keshaviah A, Brown C, Wood E, Granick L, Kimball AB. 2014. Geographic Distribution of Clinical Trials May Lead to Inequities in Access. Clinical Investigation 4(4):373–80. https://doi.org/10.4155/cli.14.21

- Sedhai YR, Sears M, Vecchiè A, Bonaventura A, Greer J, Spence K, Tackett H, et al. 2021. Clinical Trial Enrollment at a Rural Satellite Hospital during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 5(1):e136. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.777

- Woodcock J, Araojo R, Thompson T, Puckrein GA. 2021. Integrating Research into Community Practice—Toward Increased Diversity in Clinical Trials. New England Journal of Medicine 385(15):1351–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2107331

- Elsevier Staff Reports. 2013. Poll: Majority of Americans Would Participate in Clinical Trials If Recommended by Doctor. Elsevier Connect. https://www.elsevier.com/connect/poll-majority-of-americans-would-participate-in-clinical-trials-if-recommended-by-doctor

- Olivarez A. 2023. Rep. Cuellar Introduces the Rural Physician Workforce Production Act. S. Representative Henry Cuellar. https://cuellar.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=407934

- Bierer BE, White SA, Gelinas L, Strauss DH. 2021. Fair Payment and Just Benefits to Enhance Diversity in Clinical Research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2021.816

- Gelinas L, White SA, Bierer BE. 2020. Economic Vulnerability and Payment for Research Participation. Clinical Trials 17(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774520905596

- Home Visits Are Trial Participants’ Least-Favored Decentralized Approach. 2022. CenterWatch. https://www.centerwatch.com/articles/26299-home-visits-are-trial-participants-least-favored-decentralized-approach

- Nipp RD, Hong K, Paskett ED. 2019. Overcoming Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 39(39):105–14. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_243729

- Sae-Hau M, Disare K, Michaels M, Gentile A, Szumita L, Treiman K, Weiss ES. 2021. Overcoming Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation: Outcomes of a National Clinical Trial Matching and Navigation Service for Patients with a Blood Cancer. JCO Oncology Practice 17(12). https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.01068

- Desai M. 2020. Recruitment and retention of participants in clinical studies: Critical issues and challenges. Perspect Clin Res 11(2):5– https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7342339/

- Francis D, Roberts I, Elbourne DR, et al. 2007. Marketing and clinical trials: a case study. Trials. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2212650/

- Brøgger-Mikkelsen M, Ali Z, Zibert JR, Andersen AD, Thomsen SF. 2020. Online Patient Recruitment in Clinical Trials: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. https://www.jmir.org/2020/11/e22179/

- Yadav S, Todd AA, Patel AK, Tabriz BAA, Nguyen CO, Turner DK, Hong Y-R. 2022. Public knowledge and information sources for clinical trials among adults in the USA: evidence from a Health Information National Trends Survey in 2020. Clinical Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9595001/#:~:text=Sample%20characteristics&text=Out%20of%20the%20total%20sample,a%20lot%20about%20clinical%20trials

Justin Scott Brathwaite, BA, PMP, CCRP, is a Site Readiness and Regulatory Senior Specialist.

Daniel Goldstein, MSN, RN, CCRP, is a Senior Project Manager.

Erin Dowgiallo, BS, is a Senior Clinical Team Lead.

Lindsey Haroun, BS, is a Clinical Team Lead.

Karah Ashley Hogue, BS, is an Assistant Manager, Clinical Systems Operational Support.

Tracy Arakaki, PhD, PMP, PBA, is a Clinical Project Manager.