Clinical Researcher—August 2022 (Volume 36, Issue 4)

PRESCRIPTIONS FOR BUSINESS

Kris O’Brien

Drug development success is driven by a deep understanding of the disease of interest—its etiology, epidemiology, presentation, manifestations, and progression. For rare diseases, where patient populations are small and historical data collection is inconsistent and dispersed across treating physicians in diverse geographies, much of this information may be unknown. Therefore, sponsors seeking to design reliable clinical trials with relevant, clinically meaningful outcome measures may rely on patient registries and natural history studies as valuable sources of rare disease information.

In this column, we explore the distinctions between registries and natural history studies, highlighting the potential value of each in informing and shaping clinical development in rare diseases.

Challenges of Rare Disease Development

In rare diseases, developing a comprehensive understanding of the disease of interest is hampered by:{1}

- Inherently small populations

- Frequent lack of timely diagnosis

- Scarce, incomplete, or inconsistent data

- Disease heterogeneity, which complicates diagnosis, categorization, and data collection

- Lack of precedents

- Scarcity of validated methods for assessing disease-specific conditions

- Need for more careful, more extensive planning

Observational studies play a critical role in addressing these challenges and filling in knowledge gaps, creating a solid foundation of disease knowledge to support product development.

Types of Observational Studies

Unlike clinical trials, where patients receive interventions according to a well-defined protocol, observational studies do not assign participants to specific interventions and do not attempt to affect the outcome.

Observational studies are divided into two categories:

- Registry studies, which may include a broad collection of defined data

- Natural history studies, which are used for controlled, detailed collection of data that may be subject to review by a regulatory agency

While the terms registry study and natural history study are often used interchangeably, they differ in definition and application.

The Role of Patient Registries

A patient registry is an organized system for collecting, storing, retrieving, analyzing, and distributing information on individuals who have one of the following:

- A disease of interest

- A condition or risk factor that predisposes them to a health-related event

- Prior exposure to substances that are known or suspected to cause adverse health effects

A subset of patient registries is designed for a specific purpose—for example, collecting particular demographic, epidemiological, efficacy, cost-effectiveness, quality of life, or care pattern data. However, most registries are less restrictive and less structured and can be set up to collect data, including patient communications and post-marketing data.

Since registries are typically broad in scope, registry studies may be useful throughout drug development. Common applications of patient registries include:

- Collection of disease information

- Study of the standard of care or best practices

- Recruitment for clinical trials

- Observation or identification of population behavior patterns

- Monitoring of long-term outcomes

If a drug product is included in a registry study, that product must be approved, commercially available, and used in accordance with the approved labeling.

The Role of Natural History Studies

A disease’s natural history refers to how a disease process progresses over time without any treatment.{2} The objective of a natural history study is to document the course of a disease, starting just before it begins and progressing through its different clinical stages until the patient is cured, chronically disabled, or deceased.

Unlike registries, natural history studies are designed with a specific purpose, such as tracking the evolution of a disease over time, identifying factors that correlate with the disease and outcomes in the absence of treatment, or informing clinical trial design. These studies may also be used for:

- Obtaining more accurate estimates of disease prevalence

- Identifying and differentiating among disease subtypes

- Identifying demographic, genetic, environmental, or other factors that affect disease prognosis

- Identifying and assessing potential serological, tissues, and imaging biomarkers

- Evaluating and validating potential clinical outcome assessments

- Assessing the background risks associated with rare untreated diseases, providing context for assessment of potential risks associated with future therapeutic interventions

- Refining protocol design, including study duration, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and appropriate endpoints

Data collected from natural history studies may also be useful for understanding the dynamics of laboratory and clinical changes that can help identify the optimal time for therapeutic intervention.{1} Natural history studies may be especially valuable in rare disease research where it is not possible to include a placebo control clinical trial arm for logistical or ethical reasons. In certain situations, a natural history study can even serve as a surrogate for the control population, provided the study has been designed to meet the requirements for regulatory submission.

Timing of Natural History Studies

In its draft guidance document, Rare Diseases: Natural History Studies for Drug Development, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration urges sponsors to carefully consider the timing of natural history studies in the development process.{3} The guidance includes a discussion of the pros and cons associated with implementing natural history studies at various stages of clinical development. Generally, these studies are likely to be most useful if completed before initiating interventional studies, but they can also be performed in parallel with clinical trials.

Types of Natural History Studies

There are several natural history study designs, each with advantages and disadvantages. The designs may be retrospective, focused on the present, or prospective.

Medical literature reviews are the easiest, least expensive way to begin elucidating the natural history of a disease. Still, data may be difficult to standardize, and these studies may not meet natural history study objectives. Retrospective chart reviews are also relatively inexpensive, though missing and non-standardized data may present hurdles to the research.

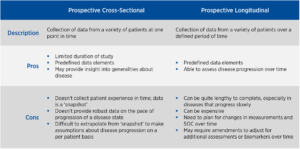

Prospective natural history study designs include cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal studies (see Figure 1). Cross-sectional studies collect data from a variety of patients at a single point in time. While these studies may provide insight into disease generalities, they do not provide any insight into the progression or patient experience. Meanwhile, longitudinal studies collect data over a prospectively defined period. These studies can be lengthy and costly, but may provide valuable information on how the disease progresses over time.

Figure 1: Comparison of Prospective Natural History Study Designs

Natural History Study Design Considerations

Though natural history studies may collect information on therapeutic interventions, it is essential to ensure that data gathering also includes measures that assess all facets of the disease of interest. When considering what data to collect, sponsors should anticipate any questions that might arise over the course of drug development. This includes disease presentation, manifestations, morbidity, and progression. Often, natural history studies include evolving protocols that incorporate plans to refine data collection as new disease knowledge emerges.{1} Ideally, the data collected should be sufficiently robust to support the development of multiple therapeutic options.

Data collection requirements, assessment type, and frequency must align with the standard of care, which may differ among providers or institutions and may even change over time. Standard of care may help inform the selection of meaningful endpoints and appropriate assessments for measuring or monitoring disease progression. It is also critical to understand how the standard of care may impact site feasibility, study duration, and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Due to regulatory scrutiny, data quality and monitoring are essential for any study subject. Even if the planned natural history study will not be included in regulatory submissions, it is critical to ensure high-quality data. While 100% source data verification is not mandatory, some level of monitoring is recommended.

Collecting and Ensuring High-Quality Data in Natural History Studies

As with interventional clinical trials, data collection in natural history studies can be performed through either local sites or one or more central sites. With local sites, data are collected by a patient’s existing provider and submitted to central data collection. While this approach limits the burden on the patient, it may introduce variability. With central sites, all study assessments are performed at a limited number of experienced sites. This approach to data collection increases consistency and helps minimize the risk of missing data or protocol deviations, but may increase the study burden if patients need to travel long distances to those central sites.

Combination models offer a hybrid approach where complex or specialized assessments are performed at central sites and routine assessments are completed at local sites. Sponsors may also opt for a patient-reported model where all assessments and data collection are performed in the patient’s home. Although this approach is the most convenient for the patient, it may introduce variability and requires significant training of in-home providers. Ultimately, the most appropriate data collection model for a natural history study will depend on the overall objectives.

Conclusion

Both registries and natural history studies play important but different roles in the clinical development of therapeutics for rare diseases. Therefore, understanding how—and when—each of these observational studies should be used is essential for guiding the design of successful clinical trials.

References

- Lapteva L, Vatsan R, Purohit-Sheth T. 2018. Regenerative Medicine Therapies for Rare Diseases. Trans Sci Rare Dis 3(3–4):121–32.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lesson 1: Introduction to Epidemiology, Section 9: Natural History and Spectrum of Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section9.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2019. Rare Diseases: Natural History Studies for Drug Development—Draft Guidance. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM634062.pdf

Kris O’Brien is Executive Director for Program Strategy in the Rare and Pediatric Diseases area at Premier Research, and has been conducting clinical research for more than 35 years in multiple therapeutic indications, programmatic areas, and corporate leadership settings.