Clinical Researcher—August 2022 (Volume 36, Issue 4)

PEER REVIEWED

Annick de Bruin, MBA; Shalome Sine, MPH; Lieven Van Vijnckt, PharmD; Alyson Gregg, MBA; Catherine Cole

Government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and patient advocacy groups increasingly involve patient and caregiver feedback at various checkpoints throughout the clinical trial process to develop research protocols with greater benefit and less burden to participants and their families.{1} Involving patients and their support network in the protocol development process can take several forms, including patient advisory boards, surveys, and interviews. However, best practices and standardized processes for developing patient-centric trials have not yet been widely established.{1,2}

In recent years, several organizations and initiatives have emerged with the intention of advancing patient engagement in drug development and/or research, including the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI),{3} the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI),{4} the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Patient Engagement Collaborative with CTTI,{5} the FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development (PFDD) program,{6} and the not-for-profit Patient Focused Medicines Development (PFMD){7} organization. All seek to increase patient involvement across the lifecycle of medical product development, including through the phases of research, and to improve trials in terms of quality, efficiency, safety, and ethical conduct, as well as in engaging all stakeholders as equal partners. The current trajectory toward greater patient involvement represents an opportunity to develop and conduct more effective research via outcomes such as realistic inclusion and exclusion criteria, lower participant burden, and patient-relevant endpoints.{8}

To create meaningful impacts, patient engagement strategies need to be put into place that result in substantive feedback and turn communication into actionable change.{9} Numerous types of patient engagement approaches exist, including community advisory boards, patient advisory boards, individual interviews, and surveys (see Table 1). Tools for implementing these models have been provided by the FDA, PFMD, the PARADIGM (Patients Active in Research And Dialogues for an Improved Generation of Medicines){10} initiative in Europe, and other organizations committed to furthering patient engagement across the lifecycle of medical product development.{11-14} For example, PFMD has published a series of toolkits, resources, and “how-to” guides for quality and effective patient engagement.{12,13}

Table 1: Exemplar Models of Patient Engagement with Industry-Sponsored Research

Among the wide range of available tools and engagement strategies, one approach Janssen utilized was to implement a long-term, recurring global community advisory board. While one-time market research activities such as interviews and surveys can and do yield actionable insights, single touchpoint projects can also limit the amount and type of data obtained and usually solicit patient feedback only on a single protocol. In contrast, the community advisory board model’s long-term focus provides the opportunity to establish a long-term partnership with patients based on trust, knowledge-building, and the reciprocity of true dialogue.

Through the Patient Voice in clinical trials program, Janssen routinely obtains patient and caregiver feedback into clinical trial design across all therapeutic areas. Because many learnings apply to more than one clinical trial, and because of a desire to build on insights in an iterative manner, the Janssen Clinical Insights and Experience team collaborated with an independent third party—the nonprofit Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP){15}—to create a standing Global Community Advisory Board (GCAB) for the immunology therapeutic area. The GCAB consisted of patient advocates with a variety of immunological conditions. The main objectives of the GCAB were to obtain feedback on strategies and solutions intended for patients, with a primary focus on clinical trial design; establish a strong working relationship between patients and Janssen; establish lines of communication with the broader community of patients with immunologic conditions that Janssen could connect with, both regularly and on an ad hoc basis; and ensure that patient-centric practices and principles are incorporated into clinical trials sponsored by Janssen.

This approach to engaging with patients aligns with industry recommendations and frameworks. It was formed to be a standing, long-term advisory panel consisting mainly of patients from around the world, and was facilitated by an independent third party (both CISCRP and Janssen personnel were active panel members). This model focused on the broader therapeutic area of immunology to promote a long-term, more impactful engagement. Thus, the GCAB provided the opportunity to explore a host of questions about Janssen’s clinical trials development and engagement strategies with a group of patient advocates in an atmosphere intended to build openness, trust, and mutual respect. The transparency and sense of trust built over time through this model were found to benefit both sides of the patient-sponsor equation.

Patients and Methods

Formation of the Immunology GCAB

Through relationships with patient advocacy groups and its own participant community, CISCRP identified a group of 11 individuals (eight women and three men) with various immunological conditions who expressed a willingness to serve on the GCAB. Some, but not all patients were familiar with the clinical trial process. Because of their experience in community and patient support groups, even GCAB members who were mostly unfamiliar with clinical trials had some knowledge about clinical research. The decision to convene an international advisory board resulted in a population of patient-advocates from seven countries across three global regions: North America (United States), Europe (Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, United Kingdom), and Asia-Pacific (India, Taiwan). Each patient advocate had a keen understanding of the specific challenges of his or her country of origin. CISCRP and Janssen intended for the GCAB to be a standing, long-term advisory panel with greater flexibility than the traditional, single touchpoint patient advisory board model. The Janssen team consisted of members in clinical research and operations roles, as well as members in patient engagement roles. Additional personnel from across the business also joined certain GCAB meetings as needed.

GCAB Activities

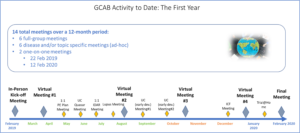

Over the course of one year, two in-person GCAB meetings were held: a kick-off meeting in February 2019 and a year-end review meeting in February 2020. In between, there were four GCAB virtual meetings held via an online platform. GCAB members also engaged in ad hoc communications throughout the year, both to provide feedback on questions that arose between meetings and as they desired to support one another.

In addition to the six full-group meetings, a further six virtual condition/topic-specific meetings were held. Furthermore, one-on-one feedback was solicited from GCAB members during in-person meetings (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Immunology Global Community Advisory Board (GCAB) Meeting Schedule

GCAB members also completed surveys and reflection exercises for Janssen to address areas of interest. These included general questions, such as the perception of clinical trials among patient groups, and specific questions that assessed the effectiveness of trial information materials, receptivity to trial-related technologies, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and planned clinical trial assessments that could increase or decrease participation.

Results

Impact on Janssen Programs

For Janssen, the opportunity to seek patient feedback on various projects over time resulted in several operational and protocol changes to clinical trial study designs that fulfilled the original aim of the GCAB. The willingness of GCAB members to respond to study materials in conversation with staff and researchers has changed some of the baseline assumptions of the trial design process. This enabled a greater focus on patient-relevant outcomes, which procedures are truly necessary to achieve the desired results, and how to inform and empower patients using materials that respect their experience of living with a condition. The decision to involve patients with a broad range of immunologic conditions—rather than any specific one—presented the opportunity to gather feedback and discuss problems consistently, without the need to pause a trial or to complete work based on a specific protocol’s schedule. This efficiency enabled changes to be implemented as quickly as possible, which further built trust among GCAB members.

Seeking feedback from GCAB members on proposed trials resulted in several straightforward actions intended to increase enrollment and retention. For example, a proposed trial involved regular trial visits for bloodwork and medical photography, as well as required patients to wear an actigraphy device to monitor adherence and physical activity. GCAB members highlighted the time burden involved in short repeat visits to a study site would limit participation by those with unreliable transportation and/or a long travel distance. Numerous concerns also arose regarding the invasiveness of the actigraphy device, as well as regarding data security (the latter particularly from European members). Ultimately, investigators chose to remove these requirements from the study.

GCAB Feedback Additionally Supported and Informed Patient Engagement Strategies

In addition to gathering and acting on clinical trial design feedback, Janssen obtained insights from GCAB members to help shape MyTrialCommunity, a website for engaging with patients enrolled in Janssen clinical trials. Member feedback was integral to the development of this initiative. They recommended the site name and suggested changing logos and adding testimonial videos from patients to explain the trial process in a non-threatening environment. In one example, a GCAB member shared personal experiences with the life-altering diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as well as a video from a patient advocacy group about the day-to-day challenges of dealing with IBD. Janssen staff were moved by these patient stories and experiences and appreciated the opportunity for open dialogue about the impact of an IBD diagnosis, as well as the impact of living with the condition on people’s lives. The Research and Development team disseminated the video throughout the research group, to drive home the real-world impacts of their work.

Trust, Awareness, and Advocacy Strengthened among GCAB Members

This integration of GCAB feedback led GCAB members to feel empowered and enhanced their engagement in the advisory board process. GCAB members expressed surprise that their input affected the trial design, as some previous patient engagement experiences had not resulted in the same level of transparency and change. As a result, GCAB members reported a resulting sense of empowerment and engagement in the advisory board process, as they could observe the impact of their feedback and how it was genuinely valued.

Overall, GCAB members reported having a positive engagement experience and gaining a greater understanding of clinical trials as well as pharmaceutical companies in general. Before joining the GCAB, some believed clinical trials to be a last-resort option where patients were treated as “just a statistic.” Their perceptions evolved as members learned more about how clinical trials work, the level of effort and care pharmaceutical companies use to implement responsible trials, and the role of clinical trials in finding new treatments for their condition. Thus, GCAB members now understood that not only were clinical trials a viable treatment option for a wide range of patients, but they were an essential component in advancing the causes and objectives of their patient community.

These paradigm shifts among GCAB members highlight the success of the GCAB model in providing a collaborative, supportive environment where GCAB members could become more engaged in and educated about clinical trials. This enhanced the quality and actionability of insights, as well as greater understanding of things that could not be changed in clinical trial design.

Consistent Communication and Transparency are Important

For many patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, barriers to research can be present from the onset of their condition journey, which can ultimately influence patients’ perception and willingness to participate or engage with clinical research. GCAB members reported difficulties obtaining a diagnosis, and once diagnosed, still dealt with feelings of shame and isolation brought on by their symptoms and the knowledge that they may never “get better.”

Outside the United States, patients reported greater difficulty obtaining information about clinical trials. This was particularly the case for smaller European countries without a robust patient organization network. Patients were frustrated by a lack of information about available trials on the part of their physicians and/or a perceived lack of interest from physicians who would not personally participate in the trial. Even when they searched online, barriers to information included a lack of clarity about where trials are available, limited country-specific public information about ongoing clinical trials, and engagement materials being available only in English.

Further barriers included an overuse of technical language by researchers. The era of molecular diagnostics (e.g., biomarkers) and treatment has added new layers of complexity to the research process, and this area of research remains too difficult for many patients to understand. GCAB members requested an in-depth, accessible explanation of what biomarkers are and how targeted therapy works.

A lack of transparency about what data will be collected from patients, how it will be used, and the risks and benefits of experimental interventions was also cited frequently. Long lists of potential adverse events can intimidate potential trial participants, especially when not accompanied by clear explanations of their true risk and prevalence. Further, patients consistently mentioned their discomfort with joining trials where they would never find out the results, whether their own or the overall trial outcomes, including not knowing whether they had been randomized to the active treatment or placebo arm of a study. The need for trial documents in plain language was another item identified by GCAB patients as an important barrier to overcome in building trust and ensuring patients are truly informed before they consent to clinical trial participation.

Meaningful Communication is a Key Component of True Patient Engagement

Meaningful communication, as identified by the GCAB, was that which either resulted in actionable strategies (e.g., adjusting inclusion/exclusion criteria, changing ads to increase diversity/representation) or clarified the parts of a clinical trial that remain difficult for most patients to understand. One such opportunity is the regulatory and informed consent process—giving patients information about the importance and function of regulatory requirements in place to protect participant safety was repeatedly reported by the patients as increasing their sense of trust as well as their willingness to engage with a lengthy consent process. Additionally, many patients were unaware of the many “moving parts” of a clinical trial that are not patient-facing, so educating patients about the time constraints for things such as data analysis and regulatory approval can increase trust in the timeline of therapeutic development. Ensuring that patients will have access to results of a study—and thus an understanding of how their time and effort contributed to the study—is also advantageous to building trust.

One unexpected outcome of this engagement model was that, by educating and empowering patients, they become more comfortable with and supportive of the clinical trial process in general. Several GCAB members reported that their new understanding of safety measures for Phase I and II trials removed their fear of being “lab rats.”

On the sponsor side, in response to GCAB member feedback, Janssen took steps in several areas. For example, a patient brochure was substantially modified to provide more comprehensive data about the purpose and conduct of clinical trials. A patient testimonial video was also modified to increase a sense of inclusivity by starting with definitive statements instead of questions.

A meeting addressing topics of digital health brought up questions about data collection and security. There was a division between GCAB members on this topic, with European GCAB members expressing greater skepticism about providing digital information about themselves than Asian and U.S. members. In response, Janssen put in place measures to increase transparency about what trial data would be collected and how the data would be stored and used. Discussion from yet another meeting spurred the development of patient educational materials to more clearly describe the benefits and purpose of early-stage clinical trials and the potential long-term benefits of these trials to patient health.

Best Practices and Learnings for Future Engagement Models

To ensure that meetings were structured, had pre-planned agendas and moderator guides, and were facilitated by an independent third party, Janssen partnered with CISCRP to implement the GCAB model. As a neutral party and liaison between patients and the pharmaceutical company, CISCRP helped establish a baseline of trust for both advisory board members and sponsor personnel. Because of its extensive experience in patient engagement initiatives such as community advisory boards, CISCRP was also able to manage the logistical coordination of GCAB meetings, ensure that the project progressed according to determined timelines, and accommodate GCAB member needs and questions in a timely manner.

Despite favorable responses about the GCAB and the approach taken, there were some limitations reported by GCAB members across several broad categories. These included: respect for patients’ time, organization of activities, information overload, burdens to patients caused by holding several meetings, a focus on English language, and a general U.S.-centric focus on materials. Although non-U.S. GCAB members had excellent English-language skills, several non-native speakers expressed discomfort with the speed of presentations, calling for a greater level of comfort with written communication to ensure that non-English native speakers are not excluded or discriminated against. Non-U.S. patients remarked that, especially in smaller countries, pathways to information about clinical trials are lacking. This presents an opportunity to explore enrollment opportunities via non-U.S. patient advocacy and physician networks.

Regardless of language of origin, patients reiterated the need for materials and presentations to be given in plain language and in easily digestible amounts. Adequate discussion was a key factor leading to patient engagement and trust in the process. Patients frequently noted the need to keep meetings—both online and in-person—organized and on a schedule that respected patients’ time constraints.

Discussion

A growing focus on patient-centered outcomes by sponsors and regulatory agencies is an opportunity to establish practices that mutually benefit patients and pharmaceutical companies and other stakeholders. The year-long experience with the GCAB provided rich, actionable insights that could not have been obtained from other stakeholders, and demonstrated that a key component tying the GCAB’s feedback together was the sense of trust built by consistent, two-way dialogue.

The opportunities for trust-building among stakeholders occur across the spectrum of clinical research. Education is a foundation of this process—issues surrounding control groups, informed consent, and the potential that results will never be published are sources of potential opacity that can be overcome by presenting clear, patient-focused information.{16,17} GCAB members consistently reported that as their knowledge increased over the course of the initiative, so did their sense of engagement, ability to provide relevant feedback, and determination to help their patient and community networks come to a greater understanding of the importance of trial participation.

Two overall themes became clear during the data review of the GCAB’s first year in operation. First, patients want more information and transparency. Throughout meeting sessions, patients wanted to know more about the purpose of clinical trials, the thinking behind different trial procedures, data collected, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. They wanted to know that results would be communicated to trial participants, and how their personal information would be used for the purposes of the clinical trial. To this end, Janssen has taken steps, such as creating educational materials about drug-development trials, with the aim of lessening the stigma of these studies as a “last resort.”

GCAB feedback highlights the importance of engaging patients in the clinical trial design process. Effective communication about how patients are centered in the conduct of a study can increase retention through trust and transparency. Patient engagement can allow researchers and sponsors to ask questions such as:

- Are there opportunities to reduce the number of procedures, especially those which are highly burdensome for patients (for example, invasive and painful procedures like biopsies, endoscopies, and blood draws)?

- How can visits and data collection be grouped to minimize travel and time burdens on participants and their support networks?

- Which interventions, either additive (such as patient comfort kits for procedure days) or subtractive (for example, requiring fewer blood draws), have the greatest impact on the participant’s trial experience?

These types of practical questions can help researchers design protocols focused on greater efficiency, minimized invasiveness, and respect for the people taking part, while still enabling the collection of necessary evidence. The actions Janssen took in response to GCAB feedback resulted in increased engagement by both research teams and GCAB members.

It is beyond the scope of this article to delve into the financial metrics of this type of partnership, but involving patients as partners is a pragmatic strategy to increase transparency of the research process and overcome disparities in health research.{18} Other groups have assessed the financial benefit to sponsors and found significant potential for savings in terms of efficiency and retention.{19} One such potential is to troubleshoot trials before they even start. Not only does this potentially increase enrollment and retention, but it can prevent costly protocol amendments. The investment in time and educational materials in this new type of engagement model was well worth the outcomes in terms of engagement and trust.

Conclusions

A meaningful partnership among the various stakeholders in any clinical trial depends on defining goals, choosing the right partners, and investing the time to ensure that all voices are heard.{20} By engaging an advisory board consisting of knowledgeable patient advocates, we were able to present and receive valuable feedback on numerous projects and scenarios, including educational materials, inclusion/exclusion criteria and other protocol elements, and regulatory and consent documents. In doing so, the sponsor received actionable takeaways, which resulted in changes to different elements of several protocols. Engaging a neutral third party to serve as primary contact for patients, ensure well-planned meeting objectives and agendas, and collate feedback helped achieve quality engagements and effectively summarize feedback.

Further, the opportunity to make changes and demonstrate them to the GCAB was a powerful motivator for Janssen staff and researchers, as was the increased understanding of the real-world, daily experiences of patients living with immunological conditions. Because the GCAB was convened as a long-term advisory body, we were able to demonstrate to GCAB members the actions Janssen took in response to their recommendations. This investment in time and evidence proved to be key in the trust-building process and was cited by all GCAB members as a major factor in their overall positive reaction to this initiative and their views on clinical research in general.

Acknowledgements

GCAB members Nandan Baruah, Alicia Aiello, Jackie Zimmerman, Janek Kapper, Lucie Lastikova, Candace Lerman, Simon Stones, Jenni Lock, and Charlotta Norgaard critically reviewed and contributed to the contents of this article. Thanks also to Cynthia Wise, retired Global Development as Portfolio Delivery Operations Program Leader, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), for her contributions.

Funding/Support: This work was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Role of the Funders/Sponsors: Janssen Pharmaceuticals worked collaboratively with CISCRP to design and conduct this work. CISCRP was responsible for the coordination, management, and analysis of the data for this research. Janssen worked collaboratively with CISCRP to interpret the data as well as to prepare, review, and approve this manuscript, and on the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Those currently active at Janssen Pharmaceuticals who were directly involved with the preparation of this manuscript are listed as its authors.

References

1. Vat LE, Finlay T, Schuitmaker-Warnaar TJ, et al. 2019. Evaluating the “Return on Patient Engagement Initiatives” in Medicines Research and Development: A Literature Review. Health Expectations 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6978865/

2. Gregg A, Getz N, Benger J, Anderson A. 2019. A Novel Collaborative Approach to Building Better Clinical Trials: New Insights from a Patient Engagement Workshop to Propel Patient-Centricity Forward. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 2168497019849875.

3. Fischer MA, Asch SM. 2019. The Future of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Journal of General Internal Medicine 34(11):2291–2.

4. Bloom D, Beetsch J, Harker M, et al. 2018. The Rules of Engagement: CTTI Recommendations for Successful Collaborations Between Sponsors and Patient Groups Around Clinical Trials. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 52(2):206–13.

5. https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-fda-patient-engagement/patient-engagement-collaborative

6. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/cder-patient-focused-drug-development

7. https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/

8. Tenaerts P, Madre, L, Landray M. 2018. A Decade of the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative: What Have We Accomplished? What Have We Learned? Clinical Trials 15(S1):5–12.

9. Boutin M, Dewulf L, Hoos A, Geissler J, Todaro V, Schneider RF, et al. 2017. Culture and Process Change as a Priority for Patient Engagement in Medicines Development. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 51(1):29–38.

10. https://www.imi.europa.eu/projects-results/project-factsheets/paradigm

11. Dewulf L. 2014. Patient Engagement by Pharma—Why and How? A Framework for Compliant Patient Engagement. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 49(1):9–16.

12. How-to Guide on Patient Engagement in Clinical Trial Protocol Design. https://pemsuite.org/How-to-Guides/Patient-engagement-in-clinical-trial-protocol-design.pdf

13. Practical How-to Guides for Patient Engagement. https://pemsuite.org/how-to-guides/

14. Patients Active in Research and Dialogues for an Improved Generation of Medicine. PARADIGM Patient EngaRgement Toolbox. https://imi-paradigm.eu/petoolbox/

16. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Guidance Series for Enhancing the Incorporation of the Patient’s Voice in Medical Product Development and Regulatory Decision Making. www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/fda-patient-focused-drug-development-guidance-series-enhancing-incorporation-patients-voice-medical

17. Jones CW, Braz VA, McBride SM, Roberts BW, Platts-Mills TF. 2016. Cross-Sectional Assessment of Patient Attitudes Towards Participation in Clinical Trials: Does Making Results Publicly Available Matter? BMJ Open 6:e013649.

18. Šolić I, Stipčić A, Pavličević I, Marušić A. 2017. Transparency and Public Accessibility of Clinical Trial Information in Croatia: How it Affects Patient Participation in Clinical Trials. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 27(2):259–69.

19. Fillon M. 2017. Strategies to Boost Minority Participation in Clinical Trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 109(4):10.1093/jnci/djx076.

20. Levitan B, Getz K, Eisenstein EL, Goldberg M, Harker M, Hesterlee S, Patrick-Lake B, Robers JN, DiMasi J. 2018. Assessing the Financial Value of Patient Engagement: A Quantitative Approach from CTTI’s Patient Groups and Clinical Trials Project. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 52(2):220–9.

Annick de Bruin, MBA, is Senior Director of Research Services, Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation, in Boston, Mass.

Shalome Sine, MPH, is Project Manager for Research Services, Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation, in Boston, Mass.

Lieven Van Vijnckt, PharmD, works in Investigator and Patient Engagement as TA Head (IMM – ID&V), Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, in Beerse, Belgium.

Alyson Gregg, MBA, is Director of Patient Insights, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), in Titusville, N.J.

Catherine Cole is Program Team Leader for Investigator and Patient Engagement, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), in High Wycombe, UK.