Clinical Researcher—October 2024 (Volume 38, Issue 5)

PEER REVIEWED

Paula Smailes, DNP, RN, CCRP; Courtney Gillespie Saslaw, MLT

Informatics competencies are important for all clinical research professionals. In 2014, the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency identified eight essential competencies, with data management and informatics identified as crucial skills for the clinical research workforce.{1} Using new technology and data sources for clinical research studies is now a normal expectation of clinical research data management.{2} When research staff are competent in their roles, the quality of their work is enhanced. With numerous information systems being necessary to execute a clinical study, what is the best way to train our research workforce? This case study provides an overview of an electronic medical record (EMR) training conversion from instructor-led to eLearning for clinical researchers at our academic medical center (AMC), and further elaborates on training initiatives after onboarding to support competency.

Clinical Research and Electronic Medical Records

Clinical researchers with a full or partial waiver of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Law for their protocol may access our EMR system. Access provisioning follows the minimum necessary rule of HIPAA, which states that covered entities may only access, transmit, or handle the minimum amount of private health information needed to complete a specific task.{3} For this reason, researchers are provisioned access to only the workflows they need in our system.

Our AMC has close to 6,000 clinical research studies in its EMR system and examples of clinical research workflows for which EMRs may be useful include such tasks as recruitment, data mining, source documentation, reporting, and research billing charge review. Data from EMRs can also promote research with information related to the effectiveness of drugs and therapeutic interventions.{4}

Key to access provisioning is training. More than 300 newly hired clinical researchers take our clinical research EMR training each year from many possible curriculums. The type of training taken matches the type of research access needed. Positive outcomes have been found from EMR training, the most common being change of learner knowledge and skills.{5} It is a policy at our organization that EMR training must occur prior to system access.

When our organization first went live with its EMR system, instructor-led training took place in a computer lab with each end user at a computer working through tasks. However, the push for healthcare organizations to convert to EMRs became the stimulus for our organization to change how we deliver our EMR training. As an increased number of onboarding staff arrived at our organization with prior experience with our Epic-based system, we began to rethink how we could capitalize on that existing end-user knowledge.

Our high-volume roles like nurses and providers were converted first, starting in 2015, and slowly over time other roles made the same conversion. By 2020, our clinical research curriculums began their conversion to eLearning with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic giving an additional push for remote onboarding.

eLearning

The conversion to eLearning is advantageous for both end-users and our training team. The benefits for end-users are that it becomes a means for training that can be taken any time, any place, and at the users’ own pace. It also serves as a source for refresher training with the same convenience. For the training team, it frees up time that would otherwise be used for classroom instruction to focus on optimization efforts. Additionally, training can be standardized within a single eLearning product, whereas in-person training across several different trainers cannot.

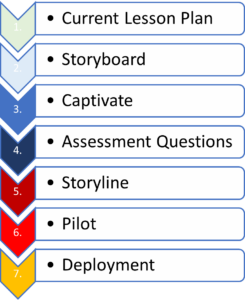

However, eLearning is a time-consuming process for development. There is a multi-step process (see Figure 1) that involves several team members (see Table 1) to ensure both quality and meaningful content are maintained as the development flows to completion.

Figure 1: eLearning Conversion Process

Table 1: Roles Needed for eLearning Development

| Role | Description |

| Principal Trainer | A content expert for workflow who assures that materials are current. |

| Instructional Designer | An eLearning development expert who assists in making the eLearning effective and compliant with established organizational templates and standards. |

| Technical Editor | This role is essential for the quality assurance process in terms of reviewing content for spelling and grammar. |

| eLearning Developer | Works to create the Storyboard, Captivate, and Storyline files (Adobe products) using the AMC’s style guide and eLearning principles established by the instructional designer(s). |

| Subject Matter Expert | An additional team member, such as a builder or someone in a leadership role, who knows workflows and targets end-users who can provide additional insight for development. |

Development Process

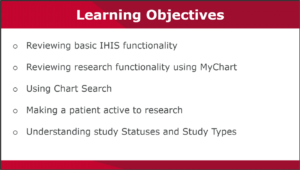

One of the first steps in eLearning conversion is the development of a design document. The principal trainer for clinical research and instructional designer at an organization should meet to discuss the lesson plan used for instructor-led sessions and determine the breakdown of the curriculum into courses and lessons. Objectives for each lesson are determined which help to drive the content (see Figure 2). Powtoon videos can also be developed, though these are typically better for content-heavy lessons versus workflow-related training. The design document is created in Excel and shows the development timeline from start to finish, as well as the progress made toward each milestone.

Figure 2: Example eLearning Objectives for Research Curriculum

Essential to the early phases of development are ensuring that the existing lesson plans and exercise workbooks are current, as well as compliance with our eLearning style guide. Given an EMR system that changes quarterly, oftentimes changes are impactful. These lesson plans serve to guide eLearning content.

Once lesson plans are ready, a Storyboard is created from them. A Storyboard is a vision board that takes the lesson plan content and places it in a PowerPoint document. Key to this phase is using the necessary templates and language, which provide standardization across multiple curriculums and clinical roles. The Storyboard includes step-by-step screenshots of workflow through which the researcher will ultimately progress.

Essential to Storyboard development is creating scenarios that are engaging and realistic. The importance of racial, gender, and age diversity should not be overlooked when stock pictures of people are included to represent patients and clinical research workers to establish clinical research scenarios.

Once the Storyboard has gone through quality assurance, it is placed in Adobe Captivate. This takes the non-interactive Storyboard and makes it into an interactive simulation. For example, if the directive is “click here,” Captivate will progress to the next slide after the researcher clicks in the designated spot, thus creating the simulation. Upon completion, the Captivate file will go through quality checks to make sure the timing and functionality are working appropriately.

While the Captivate file is being developed, the principal trainer for clinical research can be creating assessment questions. These questions quiz the researcher on content taken. The assessment questions go into a template, then through the quality assurance process to ensure standardization in verbiage, such as whether or not the questions match the objectives of the course. Assessment best practices, such as avoiding “All of the above” or “None of the above” as answer options should be considered. Ideally, having accompanying screenshots with the assessment questions can help the learner answer appropriately.

Deployment

When the assessment questions and Captivate file are complete, they are packaged and placed into Storyline. Our AMC’s organizational branding is included, then it is loaded into our learning management system (LMS) for a pilot run (see Figure 3). This ensures that the lessons within the course launch successfully, that assessment questions advance appropriately for correct and incorrect answers, and that the course objectives are included. Ultimately, this testing helps us to ensure that the course lands on the completed transcript if passing the assessment, while failed assessments should remain on the active transcript.

Figure 3: Example of Research Course in LMS with Organizational Branding

Once ready, the official launch of the eLearning is made in our live LMS. Occasionally issues arise once the training is live, such as screens that fail to advance when prompted. Resolution of these issues occurs from our eLearning team. Lesson plans are created from the Captivate files after deployment and will be used for future maintenance. Maintenance occurs every two to three years, whereby the development process is repeated except there is no Storyboard. The screenshots are updated and placed into Captivate with updates to workflows and verbiage as needed. If a major system change occurs, then a request could be made to the eLearning team prior to the standard maintenance schedule.

eLearning Satisfaction Survey

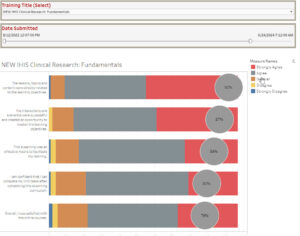

At the conclusion of each eLearning is an eLearning Satisfaction Survey. This provides the researcher an opportunity to give feedback on this method of training. The survey consists of five questions in a Likert scale format. The survey is not a requirement and will automatically remove itself from the transcript after two weeks.

One example of an eLearning Satisfaction Survey is from our Clinical Research Fundamentals course. Results show that over a 21-month time frame, most of the 110 researchers who completed the survey found the content favorable (see Figure 4). Feedback for all research curricula is monitored on a continued basis and considered when courses go to maintenance for improvement opportunities.

Figure 4: eLearning Satisfaction Results from Clinical Research Fundamentals

Initiatives After Initial Training

When a newly hired researcher is onboarded, there may be a time gap between initial EMR training and access provisioning. As more time passes, there is an increased likelihood that learned content will be forgotten. For this reason, it is important to make sure that training is taken as close to access provisioning as possible. The forgetting curve is well known, and evidence has suggested memory phases that reflect time frames of memory decline.{6} As previously mentioned, one of the benefits of eLearning is that it is a 24/7 source for refresher training, should the researcher need it.

Competency Checklist

One useful tool that can be used by management is the Competency Checklist. This checklist, created per the EMR training course, serves as a guide to determine if the researcher can show mastery of system functionality. When deficits are found, they can be learning opportunities to address with the lead trainer, educator, preceptor, or leadership to help bridge knowledge gaps.

Onboarding Sessions

Onboarding sessions are opportunities to spend 1:1 time with the principal trainer of clinical research at our AMC. These 30-minute sessions review learned content from the eLearning, but applied to the researcher’s therapeutic area. The time is spent creating study reports and doing system customization to help them find information quickly and document efficiently. These catered sessions are completed virtually to allow for higher productivity for the trainer by eliminating travel time. Researchers across our enterprise could be up to 20 miles apart, and the virtual option allows for more time onboarding instead of traveling.

Sessions are conducted using Microsoft Teams with screen sharing, which allow for system guidance, just as if sessions were conducted in person. A report is completed by the trainer on covered topics, and this can be shared with the new hire’s manager. At the conclusion of onboarding sessions, researchers are sent an email with important tools and workflows that were covered during the session.

Rounding

Rounding is an initiative that is part of ongoing optimization for researchers. As previously mentioned, our research end-users are geographically dispersed across our county. Rounding is an opportunity to meet the end-users at their location and address any system issues at a time that is convenient for them. Rounding may consist of targeted topics or address the latest system changes. A report can be done per division and shared with leadership, but can also be used as a tool to track common trends.

Training Materials

A variety of tools are used to help research end-users with workflows. Tipsheets and Quick Start Guides are condensed workflows in PDF format that can be sent to end-users when questions arise; they are targeted to specific workflows. Exercise books can be used to reinforce eLearning by providing scenarios to practice in a play environment. The resources, while helpful to end-users, must be kept current in the presence of constant system change.

Conclusion

It is important that new hires feel supported as they begin their research careers. The onboarding process can be a crucial time to help them transition to the organization and to develop knowledge about clinical research workflows and organizational policies. Including technology training, specifically on the EMR system, is at the core of clinical research execution at our organization.

The development of quality training initiatives can produce knowledge on efficient use of the system that ultimately can improve the quality of data and study productivity. While eLearning offers the benefit of convenience and easy access to refresher training, it should be noted that the development process is time consuming and involves many people to ensure the delivery of a quality training product.

Constant EMR system change means that training done as a new hire will no longer be effective in future years. Because of this, continued training initiatives must be done as a means of ongoing support, which ultimately leads to research study success.

References

- Sonstein SA, Seltzer J, Li R, Silva H, Jones CT, Daemen E. 2014. Moving from Compliance to Competency: A Harmonized Core Competency Framework for the Clinical Research Professional. Clinical Researcher 28(3):17–23. https://mrctcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/2014_6_harvard_mrct_clinical_researcher_publication_competency_framework.pdf

- Zozus M, Kahn MG, Weiskopf N. 2023. Data Quality in Clinical Research: Methods and Applications. In R. A. Richesson, Clinical Research Informatics (169–98). Springer, Cham. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330949848_Data_Quality_in_Clinical_Research_Methods_and_Applications (doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-27173-1_10)

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2013. Minimum Necessary Requirement. Health Information Privacy: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/minimum-necessary-requirement/index.html#:~:text=The%20minimum%20necessary%20standard%2C%20a%20key%20protection%20of,a%20particular%20purpose%20or%20carry%20out%20a%20function

- Dagliati A, Malovini A, Tibollo V, Bellazzi R. 2021. Health Informatics and EHR to support clinical research in the COIVD-19 pandemic: an overview. Briefings in Bioinformatics 22(2): 812–22. https://academic.oup.com/bib/article/22/2/812/6103007

- Samadbeik M, Fatehi F, Braunstein M, Barry B, Saremian M, Kalhor F, Edirippulige S. 2020. Education and Training on Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) for heatlh care professionals and students: A Scoping Review. International Journal of MEdical Informatics 142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104238

- Radvansky G, Doolen A, Pettijohn K, Ritchey M. 2022. A New Look at Memory Retention and Forgetting. Journal of Experiemental Psychology; Learning, Meomroy, and Cognition 48(11):1698–723.

Paula Smailes, DNP, RN, CCRP, (paula.smailes@osumc.edu) is a Visiting Professor at Chamberlain College of Nursing and Senior Information Technology Training and Optimization Analyst at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

Courtney Gillespie Saslaw, MLT, is a Senior Systems Analyst at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center specializing in instructional design and eLearning development.