Clinical Researcher—November 2019 (Volume 33, Issue 9)

PEER REVIEWED

Ridge Archer, MACPR; Mary Raber Johnson, PhD, RAC; Esther Chipps, PhD, RN, NEA-BC

Drug development is a billion-dollar industry featuring a variety of roles necessary to pursue the goal of product approval.{1} A crucial component within this process is well-developed, well-documented, and well-communicated study research practices. Medical writers act as key communicators for study sponsors and governmental agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency, to evaluate coherence, ethics, and efficacy of research practices and results for drugs and medical devices/diagnostics.{1–3}

Medical writers either within pharmaceutical companies or via contract research organizations (CROs) can be further divided by specific writing role and key composition types, such as promotional and/or advertising, non-promotional education/training (e.g., medical affairs), publication, labeling, and regulatory writing, as described in the following:

- Advertising and promotion utilize a unique set of regulations for postapproval communications to market the respective product to patients and/or healthcare providers; 21 CFR 202-203 in the FDA’s Code of Federal Regulations and many guidance documents direct writers in this arena.

- Non-promotional education or training materials are often geared to professional audiences, such as key opinion leaders or medical affairs professionals, respectively.

- Publication writing summarizes clinical research procedures, analysis, and results into journal manuscript formats or conference materials, such as presentations, abstracts, and posters.

- Key examples of labeling documents include therapeutic ingredients, dosing directions, and warnings on the exterior of therapeutic packaging and inserts; the core purpose is to update and list all risks and directions for safety of therapeutic use following approval.

- Regulatory writing is the development of preclinical and clinical research procedures into documents and submission packets that review and record essential study conduct, practices, and results.{2,3} Writers within this discipline ensure clarity of study statistical analyses, protocol guidelines, toxicology reporting, and completion of study and governmental agency-specific documentation and submission packets needed for approval and ongoing research practices.{2,3}

In summary, Table 1 reviews the key types of medical writing and provides brief descriptions and examples of content.

Table 1: Key Types of Medical Writing

| Medical Writing Types | Brief Description | Examples of Documents |

| Promotional/advertising | Composition of therapeutic and product information to patients/consumers and clinicians for commercial and instructional use | Promotional presentations, direct-to-consumer ads, sales aids (e.g., brochures), and digital/media promotion (e.g., websites, social media) |

| Non-promotional education/training | Composition of therapeutic and product information to educate clinicians and other medical professionals | Internal educational/ training content (e.g., advisory board slide decks) or external scientific content (e.g., exposition information, standard response letters) |

| Publication | Composition of study design/methods, data analyses, and clinical trial results of an intervention(s) or studied medical topic for peer review | Journal manuscripts; conference materials such as posters, abstracts, and oral presentations; and internal documents (i.e., publication planning) |

| Labeling | Composition of medical directions and warnings for drug use to patients and clinicians | Drug labels, package inserts/instruction pamphlets, warning boxes/lists, lists of active/non-active ingredients |

| Regulatory | Composition of study documents for use in research conduction and summary of research results | Informed consent form, study protocol, clinical study report, risk evaluation and mitigation plans |

The regulatory writer is the focus of this review, and this role can be represented by a variety of individuals from multiple backgrounds, experiences, and education.{1} However, there is a lack of published literature of the necessary proficiencies and specific tasks required of regulatory writers.

A forum held by the American Medical Writer’s Association (AMWA) in 2019 reported the need for, and difficulties associated with, organizational efforts to recruit and train medical writers in the regulatory field.{4} This paper explores and characterizes the attributes and importance of the regulatory writer role in drug development as it may pertain to small-scale pharmaceutical or biotech companies. Moreover, defining the practices and requirements of a regulatory writer can encourage interest in, and inspire novice candidates to consider joining, this field.

Select Examples of Regulatory Documents for Regulatory Writers

Regulatory writing includes a variety of documents utilized in different functions in the conduct of clinical research. The following sections summarize several core research documents that are chiefly written by regulatory writers.

Informed Consent Form

Informed consent forms (ICFs) are the main documents used by study site personnel for familiarizing potential volunteer subjects with the details of a specific clinical trial. Per international and governmental agency criteria, such as FDA’s 21 CFR 50, volunteers cannot proceed into the study protocol activities without first providing voluntary consent via the ICF, after having a discussion about any and all risks associated with study interventions, as well as about the participant requirements for completing the study. ICFs should include information on any possible adverse events and on the study’s purpose/practices, so regulatory writers must have insight and knowledge of the study protocol to ensure all the study parameters are summarized.

From a participant perspective, appropriate “understanding” of an ICF is imperative to adequately inform the participant of risks. There are different levels of understanding, including objective vs. subjective understanding (i.e., correct knowledge vs. personal impression of facts) and general understandability—all of which need to be considered in ICF creation.{5} Further, a study comparing ICFs over a period of 17 years for rheumatology studies identified a need for ICFs to be written between a third- and eighth-grade reading level.{6}

Conciseness is another important component in ICF creation, whereby higher page counts in ICFs result in participants being less likely to fully review document content.{6} Developing and abiding to structural ICF templates can assist regulatory writers so that content is full and clear.{7} Additionally, regulatory writers need to reliably incorporate multi-disciplinary feedback (e.g., from legal experts and clinicians) all while ensuring the participant will fully understand the document.

Study Protocol

Regulatory writers help to develop the protocol’s explanations of guidelines and study procedures with oversight and input from the study investigators.{2,3} Protocols usually follow a generalized structure that includes sections on therapeutic background, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation, treatment formulation and administration criteria, toxicities and reporting criteria, statistical considerations for efficacy determination, and appendices to summarize section content in figure and tabular form (21 CFR 312).

Regulatory writers also assist with the memos and amendments to the study protocol to establish additional information and altered directions for therapeutic use and minimization of risks. Regulatory writers must ensure these modifications are articulated coherently and be responsible for version control across affected documents (e.g., protocol sections and study supplemental materials)—all in a timely fashion.

Clinical Study Reports{8}

Clinical study reports (CSRs) act as comprehensive summaries of the efficacy, accumulated toxicity, and other statistical outcomes of clinical data, and are one of the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) E6 Essential Documents following a clinical trial. Regulatory writers are tasked with composing these reports about the safety and efficacy raw data outputs, which can be quite extensive with a multitude of statistical variation.

Per FDA guidance and ICH E3 criteria, CSRs should specifically include participant demographics, review of each proposed outcome, and review of adverse events that have occurred. Regulatory writers require a strong understanding of guidance documents/guidelines for characterizations and completeness over the outcomes of statistical analyses and tabular and/or graphical constructs.

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies{9}

Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) are developed as guides to educate consumers about warnings/safety issues concerning a drug and to give specific directions for therapeutic use. REMS plans have become a requirement for certain pharmaceutical products since initiated by the FDA Amendments Act of 2007 in order to impose greater safety measures on those therapeutics with seemingly higher risk-to-benefit levels. Regulatory writers document step-by-step instructions and/or safety precautions for patient use that would also be included within the New Drug Application (NDA) submission review to FDA.

Additional FDA Submissions{10,11}

Governmental agency submissions for clinical trial initiation or drug marketing require completion of specific forms and attenuation of several different study documents within the submissions. Regulatory writers often develop these large submissions, such as for Investigational New Drugs or NDAs, assembling investigator summaries, protocols, CSRs, integrated summaries of safety, and other sources of information. Amendments to any of these documents require complete updating and re-submission of the documents with a brief summary of the submitted changes.

Core Expertise of a Regulatory Writer

Inherent Proficiencies

In order to identify an individual’s interest or suitability to the role of a regulatory writer, an implicit set of expertise must be demonstrated. The role requires collaboration with many members of the research team, such as the sponsor, research site investigators, statisticians, research managers, and/or coordinators. Regulatory writers in pharmaceutical companies or CROs often have direct communication among these team members by way of telephone, in-person contact, and/or e-mail to be able to obtain, verify, and deliver content for institutional review board, sponsor, and/or governmental agency review submission. Below are key proficiencies often not evident with merely a degree or certificate:

- Clear and accurate communication: Content must be written in a manner that is comprehensible to the entire research team. For example, protocols used to describe the intricacies of a clinical study should be written to allow for all researcher roles to properly understand each section. Clarity and concision are valuable characteristics, especially in composition of study documents for general audience (e.g., ICFs). Additionally, regulatory writers often interact with various disciplines, making professional and clear communication skills vital to this role.

- Agility and reliability: Timeliness is essential to ensure study conduct meets requirements for submission. In accordance with governmental specific regulatory documentation, regulatory writers must have awareness of submission details and deadlines. Regulatory writers need to respond to rapid changes in protocols and other documents that require fast updates, making adaptability and efficiency important skills. Additionally, deadlines are often immovable (e.g., following FDA approval or for NDA submission), elevating the need for project and time management skills.

- Data comprehension and dissemination: Volumes of raw data need to be dissected and accurately communicated in many types of regulatory documents. Regulatory writers are required to have a basic understanding of statistics and medical information in order to choose the most appropriate outputs that convey a true reflection of the trial (e.g., protocol, results in CSR).

- Document management: Lastly, regulatory writers are in charge of the collection, recording, and management/upkeep of various regulatory documents that are required by law per governmental agency for ethical review of drug marketing. These various documents require proper organization and time-sensitive submission per report type. Additionally, requests to update study details require all regulatory documents and components (sections, tables, figures, and supplemental materials) to be edited accordingly.

Academic and Real-World Experience

To be successful, regulatory writers harness various skills in order to provide detailed and appropriate regulatory document compositions by accessing their education, research experience, and knowledge of regulatory science.{2,3} The following summarizes key areas of expertise, with some overlap possible:

- Formal education: Regulatory writers must have a solid educational background to demonstrate adeptness for writing within the respective specialty. A master’s degree and/or a connection to clinical research is desirable in order to obtain competencies of reviewing and interpreting statistical data results; moreover, the ability to simplify all research procedural communications to the variety of research roles is essential. In an assessment of regulatory job postings from 2009 to 2011, 68% of those analyzed required a scientific degree.{3} However, it should be noted that an advanced degree is not always required, and that work experience is a significant factor for success.

- Editorial and software competence: Regulatory writers should also be equipped with refined editorial skills, since they verify and edit a multitude of documentation to reduce likelihood of errors and ensure completeness. As noted earlier, superb communication skills are needed for computation and interacting with the research team regarding expectations and expert analyses of data such as within CSRs, safety reports, or amended documents.{2,3} Each company may also utilize its own software for data outputs or document containment; hence the regulatory writer should be familiar with and comfortable traversing many types of software. These skills can be learned through literacy courses and/or onsite experience per preferences of the sponsor and/or governmental body.

- Real-world training: Direct research experience within the topics related to clinical research (e.g., oncology) is also highly valuable in order to more easily translate and utilize verbiage associated with the evaluations of therapeutic safety and efficacy results (e.g., pharmacovigilance, toxicity reports). This experience can also provide the regulatory writer with knowledge of the clinical research workflow and previous completion or orientation to respective documents. In addition to working experience within the clinical research field, continuing education courses on clinical research practices from organizations such as the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society (RAPS), Drug Information Association (DIA), and the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) can be utilized. Networking among clinical research professionals and medical writers is another valuable experience that can help to increase awareness of, and connect a regulatory writer to, the aforementioned areas.

- Regulatory expertise: Regulatory writers require deep understanding of regulations governing research conduction, as well as of the respective governing bodies.{2,3} A thorough understanding of regulations and guidance documents is crucial for content development, along with governmental agency–specific expectations for reporting and submitting those documents. Knowledge of regulatory requirements can be demonstrated by previous work experience, education, and/or professional certifications such as Regulatory Affairs Certification (RAC) from RAPS. Experience in governmental regulatory policy, statistical methodology, biological mechanisms, therapeutic indication, and pharmacology are other desirable competencies for a regulatory writer.{2,3} Work experience in these areas allows for a more seamless transfer of data and an accurate data “storyline” in a wide variety of document types.

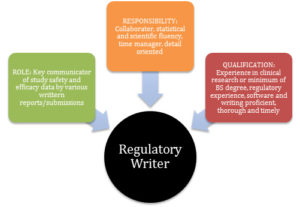

In summary, Figure 1 reviews key elements of a regulatory writer by role, responsibilities, and qualifications.

Figure 1: Key Elements of a Regulatory Writer

Conclusion

Regulatory writers have been identified as an important component of clinical research, and may act as the main communicator among the researcher roles and governing bodies concerning required research procedures and reports. An efficient regulatory writer demonstrates expertise in clarity and attention to detail, timeliness, and collaboration.

Pharmaceutical companies and CROs may approach the regulatory writer’s responsibilities with a greater concentration on specialized regulatory writing assignments. In addition, lengthy research documents can be assigned to a group of regulatory writers rather than an individual, depending on submission timelines and individual workloads. As such, written communication is the crux of successful regulatory writers’ output—within their team, to governmental bodies, to clinical study staff and investigators, and possibly to study participants/patients—with the ultimate goal of patient safety throughout a product’s lifecycle.

References

- Hager Y. 2019. Medical communications: the “write” career path for you? Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a032953

- Clemox DB, Wagner B, Marshallsay C, et al. 2018. Medical writing competency model – section 2: knowledge, skills, abilities, and behaviors. Ther Innov Reg Sci 52(1):78–88.

- Haisel-Stoehr S, Schindler TM. 2013. Different competencies and skill sets for regulatory medical writers and publication writers. DIA Euromeeting 2013: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG.

- Affleck JA, Kryder CL, Speigel K, et al. 2019. Preparing for the future of medical writing in biopharma: AMWA’s inaugural medical writing executives forum. AMWA Journal.

- Bossert S, Strech D. 2017. An integrated conceptual framework for evaluating and improving “understanding” in informed consent. Trials 18:482. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-2204-0

- Mora-Molina H, Barahas-Ochoa A, Sandoval-Garcia L, et al. 2018. Trends of informed consent forms for industry-sponsored clinical trials in rheumatology over a 17-year period: readability and assessment of patients’ health literacy and perceptions. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 48:547–52.

- Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, et al. 2001. Quality of informed consent: a new measure of understanding among research subjects. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:139–47.

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). 1996. Guidance for Industry Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm073113.pdf

- Office of Communications, Division of Drug Information Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration. 2019. REMS Assessment: Planning and Reporting Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM629743.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2017. Investigational New Drug (IND) Application. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/approvalapplications/investigationalnewdrugindapplication/default.htm

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2016. New Drug Application (NDA). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/howdrugsaredevelopedandapproved/approvalapplications/newdrugapplicationnda/default.htm

Ridge Archer, MACPR, (archer.237@buckeyemail.osu.edu) is a Clinical Research Associate at Medpace, Inc.

Mary Raber Johnson, PhD, RAC, (johnson.6844@osu.edu) is an Assistant Clinical Professor at The Ohio State University, College of Pharmacy.

Esther Chipps, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, (chipps.1@osu.edu) is a Clinical Nurse Scientist and Associate Professor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and College of Nursing.