Clinical Researcher—May 2021 (Volume 35, Issue 4)

PEER REVIEWED

Paula Smailes, DNP, RN, CCRP

The use of computer systems to monitor and document research participant care is essential at academic medical centers (AMCs). Enhanced features of electronic health records (EHRs) can facilitate research workflows such as data mining, research recruitment, adverse event tracking, and research billing. While initially developed to be patient-centric, the role they serve with respect to research and discovery cannot be denied. Considering the vast amount of clinical data they collect, an important role of EHRs is how they identify whether new interventions in healthcare delivery lead to improved outcomes, along with health savings.{1} Further expanding on that point, it has been found that clinical trials conducted with EHRs may have increased generalizability, while requiring less time and money to conduct.{2}

However, while there are historically known challenges of EHR use for research,{3} no one imagined the challenges that a pandemic would bring. With the onset of COVID-19, researchers were forced into workflows for which we had not planned. While many workers were sent home in March 2020 to reduce exposure and increase safety, research operations at their institutions often needed to continue virtually. Research leaders around the world were forced to make quick decisions on how to continue to support the established research infrastructure. This became especially true with newly hired staff in the process of onboarding.

One essential onboarding need at any AMC is EHR training for researchers, followed by ongoing support through optimization. Training is the foundation for system use. This content delivery focuses on customization and efficiency, along with research workflows that can be accomplished by the system. Despite this critical role of this training, COVID-19 pushed institutions to determine how effective training for researchers could continue during a pandemic when physical distancing is a necessity. The following sections reflect lessons learned at the author’s institution—a medical center based within one of the largest U.S. public universities.

Training

Before the pandemic, EHR training classes were held in a computer lab where new hires had their own computers and could actively engage in the system, while an instructor demonstrates workflows on a projected screen. This is known as instructor-led training. Less than one week after being forced into working from home, the first research EHR training class at our AMC needed to be taught. After considering a physically distanced, in-person approach vs. a remote, virtual training, the decision was made to go virtual.

Because we could not guarantee that onboarding researchers would have two monitors (one to observe virtual training and one to simultaneously follow along in the play environment), we needed to resort to a system demonstration. This placed more onus on the researcher to practice workflows in a “play” environment. By capitalizing on software such as Webex™ and Microsoft Teams, the remote training class could be conducted successfully. Using features such as screen sharing, chat, and hand raise, this format has the ability to be interactive similar to in-person training.

Aside from the method of delivery, no other changes were made. Session offerings continued to be every two weeks and available as self-enroll in our learning management system, or staff could enroll by phoning our training center. The content delivered did not change. Class sizes reached up to 20 attendees and were not capped, which was typical of in-person training. A total of 359 research attendees participated in two virtual training classes across 54 sessions taught during the first 12 months of virtual training.

Benefits and Lessons Learned from Virtual Training

There were several advantages to the virtual training. First, it offered end-user safety when they remotely joined the class from home. This also helped to ensure safety for training staff and eliminated travel time for commuting and parking, which can be costly. Minimal computer requirements existed for participants, but they did need to download software to view the training.

While there were benefits to virtual training, there were many lessons learned along the way. Prior to each virtual session, an e-mail message was sent to encourage users to attend from a quiet environment that was free from distractions. It also included electronic links to training materials and the phone number of the training center should there be a need for technical help. This is key, because there were instances when the attendee had computer issues and attempted to call and/or e-mail the instructor, who was otherwise teaching the class and not available to help.

In the first few weeks, the virtual classroom became overloaded due to demand on the system. It was necessary to reschedule one class due to technical difficulties. These issues were resolved quickly and did not persist over time.

A classroom etiquette also needed to be established. Many users wanted to keep their webcams on, but attendee behavior led to a request for all to turn them off. Examples of such behavior were trainees who were mobile or who had pets and children attending sessions. The absence of a webcam view eliminated distractions and made the demonstration the main focus of attention. For this same reason, a request was made for attendees to mute their lines to eliminate background noise, with the clarification that they could unmute and ask questions at any time.

Evaluating In-Person vs. Virtual Training

When the classes transitioned to virtual training, onboarding researchers were asked to complete the same post-class evaluation as those who attended the in-person training classes. Evaluations used a 5-point Likert scale, with 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neutral, 4=Agree, and 5=Strongly Agree. The post-class evaluation was used as a quality improvement tool to provide feedback on the course content and instructor. This tool is standard for the multitude of EHR training classes taught at the organization. It became especially important to receive this feedback given the new format of instruction.

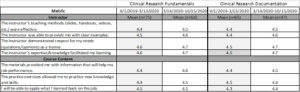

After six months of virtual training, an investigation was made as to how it compared to in-person training held during the six months prior to the pandemic shutdown. Using the mean scores of post-class evaluations, results showed that there was little difference in end-user satisfaction of both the instructor and class content (see Table 1). The learning management system is limited in terms of only providing the mean and number of respondents with the aggregate data, without information on data variability. Also, not all attendees completed an evaluation.

Table 1: Clinical Research EHR Training Evaluations Pre- and Post-Pandemic

Qualitative Feedback

In addition to quantitative results, the post-class evaluations offered researchers an opportunity to provide qualitative feedback. Recurring themes included:

- Provide directions for accessing the play environment prior to training. This allows for researchers to practice workflows prior to class and come prepared to ask questions.

- Provide a playground exercise as homework after class.

- Request for one-on-one sessions after initial training.

These suggestions for improvement were incorporated into the virtual training. The meeting appointment was enhanced to include detailed information for accessing the playground environment should users want exposure prior to the session. This information is also part of the post-training e-mail reminder encouraging attendees to review workflows.

Playground exercises are in development for specific research teams. Research leaders assist with content and scenarios.

Attendees are given the trainer’s contact information to request one-on-one sessions at any time after training.

eLearning Conversion

Prior to the pandemic, EHR training for clinical researchers was slowly being converted to electronic learning (eLearning). This format exists as computer modules that are housed in our learning management system and done independently by the researcher at any time. Our initial research EHR class converted was a research scheduling class. Three weeks into the pandemic, the research billing EHR training conversion was complete and deployed for end-users. This became a great satisfier for research leadership to know that training could be completed conveniently for staff.

The remaining two classes—system basics for researchers and documentation—will be completed by the end of the calendar year 2021. The benefits of a training conversion from instructor-led to eLearning include increased learner satisfaction, substantial return on investment, and an ongoing means of refresher training. It allows learners to review information at their own pace from any location and at any time, whereas live, instructor-led training is limited in format by typically being done at a scheduled time in a computer lab where the instructor leads the class through workflows as attendees follow along on their own computers.

Optimization

Optimization refers to the process of ensuring that after training has occurred, EHR end-users optimally use the system. This could be in the form of personal customization, efficiency, satisfaction, and awareness of ongoing system changes and functionality updates.

New Hire Follow-Up

New hire follow-up from training was already established prior to the pandemic and continues in the same fashion, but virtually. The importance of this program is to allow researchers time to access the system and understand their responsibilities, then further assist in areas such as customization to their workflows and specific therapeutic areas, along with reporting. The goal is to improve researcher satisfaction and efficiency, but also to make them feel supported in their new roles as they transition into the organization. An EHR competency checklist is used to ensure that the newly hired researcher is using the basic system features taught in the EHR training class.

Chart Audit Tool

Approximately one month into the pandemic, a meeting with research leadership revealed an area of opportunity. Since many research studies were temporarily shut down, staff were working from home and in some cases, needed remote work to do. An EHR audit tool for research was developed. This tool was designed to be used for consented patients with EHR as a source document and serves as a quality improvement tool to ensure all records are audit-ready. Designed in Microsoft Excel, each study gets its own tab, with consented patients as columns and audit features as rows, which included metrics such as:

- Are visits within the study protocol window?

- Is a consent note documented?

- Has the investigator reviewed adverse events?

- Verify inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure the patient qualified at the time of enrollment. Have any new events impacted eligibility?

- Are there any open notes that need to be signed?

- Has study drug accountability been documented?

A researcher self-assessment was included with the audit tool, so that individuals could not only audit charts, but their own EHR knowledge. If a researcher finds that he or she is not strong in some system features or has forgotten certain functionalities, a link to training materials in the tool points to the workflow for review.

COVID-19 Research

As studies restarted, researchers found themselves needing new workflows related to COVID-19 research and the EHR. Much of our organizational research is conducted on an outpatient basis, yet many COVID-19 studies were inpatient-specific. This led to researcher outreach and support for changes to their EHR usage habits. Issues of data privacy and security that arose were handled by leadership.

Telehealth and eConsent

For studies to continue, many clinical researchers turned to remote workflows and needed additional assistance with documentation efficiency related to telehealth practices. One group customized its flowsheet build to incorporate phone contact information, and this caused enough change in the original workflow to necessitate revised training documents.

Researchers also engaged in new ways of consenting; some chose to use the EHR to send research consents for review or utilized REDCap® for electronic consenting.

Research End-User Support

Research Teams

One consideration was the quarterly updates made to the system. While these occurred prior to COVID-19, the communication of changes afterward needed occur remotely. Turning to “super users” of the system, or designated EHR contacts within groups, allows for improved dissemination and a point of contact. These users meet monthly with the Principal Research EHR trainer to review emergent issues, recurrent themes, and educational tactics.

Individuals

Some areas also had multiple team members that needed individual support. Conducting one-on-one EHR support remotely isn’t too different from doing so in person. Using screen-sharing software allows trainers to see an end-user’s screen and instruct accordingly. This promotes work efficiency from both parties by eliminating travel time and conserving work time over the course of a day. As these optimization sessions are completed, they are tracked in a report and shared monthly with leadership.

Conclusion

The need for technology training continues despite the presence of a pandemic. In fact, the pandemic has provided opportunities to further engage in technology in ways not previously recognized and uncovered new and evolving needs that can be addressed with continuous, virtual EHR training and optimization.

As we have shown, capitalizing on virtual training resulted in little difference in mean evaluation scores vs. an in-person, instructor-led approach; however, the hope at our organization is to continue the training conversion to eLearning. When all is said and done, end-user support is just as crucial now as it was prior to the pandemic.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5226988/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6351244/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002870318301388?via%3Dihub

Paula Smailes, DNP, RN, CCRP, (paula.smailes@osumc.edu) is a Visiting Professor at Chamberlain College of Nursing and Senior Information Technology Training and Optimization Analyst at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.