Clinical Researcher—August 2024 (Volume 38, Issue 4)

PEER REVIEWED

Anthony Chew, MS

In clinical trial operations, clinical research associates (CRAs) serve as the primary liaison between study sponsors and sites by monitoring and verifying data to ensure accuracy and adherence to protocols. They collaborate with investigators, conduct site visits, and maintain strict documentation to guarantee the integrity of a trial. The CRA position, while highly sought after, is also one that many professionals have difficulty obtaining, despite there being many job openings for the role in the industry. This dilemma was noted in a recent Clinical Researcher article by Meghan Francis and Andrew Pucker,{1} which looked at how even CRA hopefuls with a graduate degree and experience at the site level may find difficulty securing a position as a CRA, due to the fact that many companies desire someone with at least two years of experience in a direct role as a site monitor. Of course, to gain experience as a site monitor, one must first be hired into the position of a CRA, hence the Catch-22 nature of the situation experienced by many.

The Survey

On April 1, 2024, an electronic survey conducted as part of the author’s graduate school studies was distributed to approximately 2,000 individuals who were either currently a CRA or held a previous position as a CRA. The survey was a combination of multiple choice and free response questions that investigated information such as the background of the CRA, the type of employer that initially hired them, the training process that the new CRA underwent, and any advice that they might have for aspiring CRAs (see Table 1). After one week, 59 qualified CRAs and former CRAs had completed the survey. Among the respondents, experience in the clinical research field ranged from two years to more than 25 years, with the average experience being nine years in the field. Thirty-six of these respondents were current CRAs whereas 23 were former CRAs who had since moved on to a higher position.

Select respondents were chosen for a follow-up interview to further explore their experiences and how they shaped the clinical research professional that they are today. Interviewees were selected with the objective of having a diverse set of CRAs of different experience levels and exposure. For example, one CRA was selected for their experience as a clinical research coordinator (CRC) prior to being employed at a large contract research organization (CRO), whereas another CRA was selected for their experience as a clinical trial assistant (CTA) at a small sponsor start-up. Those interviewed were asked to weigh the advantages/disadvantages that their specific experience gave them, as well as to further clarify some of their responses provided in the initial survey.

Table 1: Survey Questions and Response Options

| Question | Response Type/Options |

| First and Last Name (Optional) | Free Response |

| Preferred E-mail Address (Optional) | Free Response |

| How many years have you spent as a CRA? | Free Response |

| How many years have you spent in the field of Clinical Trial Operations as a whole? | Free Response |

| Current Job Title | Free Response |

| Current Employer (Optional) | Free Response |

| Please list the name of your employer who gave you your first experience as a site monitor. (Optional) | Free Response |

| Was this employer who gave you your first experience as a site monitor a sponsor or a CRO? | Multiple Choice:

· Sponsor · CRO · Other: (Free Response) |

| What was the approximate size of the organization at which you were employed for your first experience as a site monitor? | Multiple Choice:

· 1-200 Employees · 201-500 Employees · 501-1,000 Employees · 1,001-5,000 Employees · 5,001+ Employees |

| Please select the option that best describes the pathway you took in becoming a CRA. | Multiple Choice:

· A. CTA for sponsor/CRO –> CRA · B. CRC for site –> CRA · C. Internal Company Transfer · D. CRO Bridge Program · E. Other: (Free Response) |

| If you selected C, D, or E in the question above, please use the space below to clarify. If you selected A or B, simply put N/A. | Free Response |

| Please describe the training/qualifications process you underwent for your first experience as a site monitor. How did you go from having no experience to becoming qualified and performing an independent monitoring visit? | Free Response |

| What are three important skill sets you believe would be important for becoming or working as a CRA? Explain what you did or are doing to develop/hone these skill sets. | Free Response |

| Do you have any other advice for someone looking to break into the clinical research field? | Free Response |

| I am looking to schedule a 20-minute Zoom interview with individuals who are willing to further share their clinical research career experiences. Are you open to being interviewed? | Multiple Choice:

· Yes (If so, please ensure you provide your email in question 2) · No (Thank you for participating in this survey!) |

Who is Hiring First-Time CRAs?

Large Organizations

Results showed that most respondents (72%) obtained their first position as a CRA at a larger organization (1,001 employees or more). According to those who were interviewed, a benefit to beginning their career as a CRA at a larger company is the robust systems and training protocols in place. “Being trained at a bigger company was great for me, because bigger companies tend to have better processes in place [in terms of] better systems: they’re a little more organized…,” commented a respondent who first began their CRA career with Quintiles (now IQVIA). A current CRA had similar remarks: “The benefits of coming into a large organization that’s been around for awhile would be that they have a very systematic way of doing things. This is the plan. This is how we’re going to train you—whatever it may be—because they have a large quantity of people. They have a very established way of completing training and running through [all the trainees].”

CROs

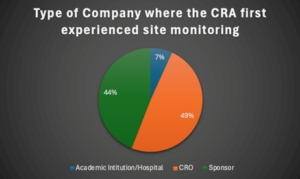

CRAs who began at a CRO had slightly more representation (49%) in the survey, as opposed to those who began at a sponsor organization (44%). A small minority of respondents began at an academic institution/hospital (see Figure1). CROs are companies that are contracted by the sponsor to perform specific trial tasks, such as site monitoring. Often, CRAs who are employed at CROs will simultaneously work on multiple trials for different sponsors at once (defined as a “full-service alignment”; working with only one sponsor is referred to as a “sponsor-dedicated alignment”).

One CRA recalled how working in a full-service alignment allowed her to observe various processes between companies and focus on which processes work best. They remarked that the training process for CROs was the “gold standard.” Indeed, the article by Francis and Pucker outlined this gold standard by recounting the growing practice of CROs to develop training programs that bridge the gap in experience for less-experienced CRAs.{1} A CRA who recently completed such a program with Premier Research compared the primary motives of a CRO as being one that prioritizes the development of the employee, versus the primary motives of a sponsor being one that prioritizes the product.

To elaborate, providing quality personnel (including CRAs) is essential to the success of the CRO, because the quality of their personnel determines the size of their customer base. As such, one viewpoint suggests that a CRO has more motivation than a sponsor organization to put more resources and training into developing quality CRAs.

The consistency of the qualification process amongst CRAs who began at a CRO was reflected in the results. For those who went in-depth about the training process, respondents of different CROs including IQVIA, PPD, ICON, and more had all cited similar training processes despite having no relation to one another. These training processes included classroom learning and online modules/certifications; as well as in-person observational training, which may have included shadowing senior CRAs on a monitoring visit and accompaniment on the new CRA’s own initial monitoring visits before being “signed-off” by their supervisor.

CRA training on the sponsor side yielded more inconsistent responses. While there were many respondents who indicated having experienced some sort of observational training, there were also multiple responses that indicated having only been assigned an online module and protocol review prior to conducting their first visit and then learning from experience going forward. One respondent stated that they received “no formal training.” Even more concerning than the inconsistency in qualifications was the inconsistency in the positions themselves. One respondent had indicated their current title as that of a “Clinical Research Associate II” for a sponsor organization, but also indicated that they did not perform onsite monitoring as part of their duties, nor had they been trained on such.

Still, respondents suggested that there were various benefits to being employed at a startup. One respondent who began his career as a CRA at such an organization described their experience as one that had great risks but one that was also rewarded with greater experience: “You have to wear many hats at a startup. That exposure, in and of itself, gives you a lot more opportunity to get experience in different sections of the clinical trial. You might do things in study start-up, you might do things in monitoring, and you might also get exposure to things like budgets and contracts. So you can get all that experience, all at one time, at a smaller company as a startup. If you go to a bigger company, they already have a structure. They already have training programs for your CRAs to go through, and most of that is going to be focused on monitoring.”

A respondent who is now in a director-level position shared similar sentiments. While starting with a smaller company was not great for their career as a CRA, it provided much cross-functional knowledge in the biotechnology industry as a whole. It also gave access to more personalized mentoring—even in terms of receiving feedback from the company’s vice president at the time.

Figure 1: Type of Company Where the CRA First Experienced Site Monitoring

Options Leading Down the CRA Pathway

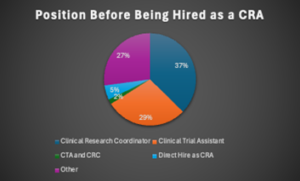

More than two-thirds of respondents were observed to have held positions as CRCs or as CTAs prior to their career as a CRA (see Figure 2). The Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) offers a “Ready, Set, Clinical Research!”{2} toolkit recognizing these two positions as common entry points into the field of clinical research. CRCs support, facilitate, and coordinate the daily research activities on the site end. On the sponsor end, CTAs provide administrative and project tracking support for the clinical trial.

Starting as a CRC

Among the respondents who were former CRCs, almost one-third cited their experience as CRCs to have played a major role in helping become an effective CRA. One such respondent highlighted their experience as a CRC as one that allowed them to have a greater understanding of what goes on at the site and have greater empathy for the site personnel when mistakes occur.

Another respondent placed emphasis on the industry knowledge their experience as a CRC gave them: “You’re able to build a really solid foundation of the regulatory requirements at the site level: Building an ISF (investigator site file) and becoming familiar with all the different essential documents that you need to collect for all your investigators.” They also recognized how directly interacting with both the patient and the site investigator developed their communication skills as well as their knowledge of the oncology field as a whole, such as the process of obtaining and reviewing pathology scans.

Starting as a CTA

Respondents who had experience as a CTA also indicated its benefits. For one, beginning their career as a CTA provided the best quality of work as well as had more direct access to upward mobility—specifically when employed by the sponsor: “When you work for sponsors directly, you’re able to decide to work on something you care about, and you get to be a lot more invested in the projects you’re on. On the CRO side, you get to see a lot of different studies, you get to be involved in a lot of different things. But also you don’t get a lot of choice about what you’re working on. I’d say the same is true as a CRC. I do think one benefit of being a CRC is that if you’re interested in going into the medical field, that can be a really good bridge, because you’re working with patients and physicians in a clinical setting. But there’s less of a job ladder. [For example, a CRC] is never going to become the PI (principal investigator)… there isn’t quite as much room for [direct] upward mobility.” Since they are on the sponsor end, a CTA has the potential option to be promoted into the CRA position, whereas a CRC must leave their current employer to advance into a CRA position.

Figure 2: Position of the Employee Before They Were Hired as a CRA

Relevant Skills

Characteristics related to communication skills (40 responses related to “communication,” “soft skills,” “relationship building,” etc.) and attention-to-detail (31 Responses) were listed by most respondents as important for being an effective CRA (see Figure 3). These traits were verified as directly applicable to the position of a CRA amongst the interviewees. For one respondent, communication is a core aspect of maintaining a good relationship with the site so as to “work together with them and not against them.” They also highlighted attention-to-detail as the “core of what monitoring is,” including tasks such as reviewing the ISF, regulatory documents, or source data verification.

Figure 3: Word Cloud Diagram of the Essential Skills that CRAs Considered Important for Their Position

Takeaways for the Aspiring CRA

Limitations of the survey were its anonymity and sample size. To encourage more CRAs to respond to the survey, certain questions (such as those pertaining to the respondent’s current or past employers) were considered optional to preserve confidentiality. This prevented any analysis on the specific organizations that the CRAs were employed by. Moreover, future studies could strive to obtain a higher number of respondents (N>59) to gain a clearer landscape of the CRA position.

It should be noted, however, that the purpose of this survey was not to provide a definitive judgment of where or how CRAs are hired, but rather to point the aspiring CRA in the “general direction” and offer insight as to the advantages and disadvantages that each type of experience provides.

While there is no “wrong” pathway to become a CRA, the responses would suggest that the ideal pathway to becoming a CRA is to start out as a CRC, then join a large CRO as a full-service alignment CRA, and then to secure a CRA position with a sponsor. This pathway optimizes the ability for the potential candidate to receive as much experience as possible—first to understand what goes on at the site, then to receive training that is consistent with the industry at a CRO, and finally to understand trial operations at a higher level with the sponsor.

Obviously, this is easier said than done. Some professionals may have trouble even obtaining the CRC position. When asked if they had any advice to give to the aspiring CRA, respondents recommended finding ways to gain experience in the clinical research field, networking, and becoming more educated in the field.

If one is unable to gain direct clinical research experience, the next step would be to develop the relevant skills that are important for the CRA, such as demonstrating communication skills, attention to detail, and any other skills listed in Figure 3. For respondents who did not have CTA or CRC experience, this might have meant working in the laboratory, handling the clinical samples themselves, and demonstrating the ability to adhere to the protocol of the trial.

Networking is also a valuable tool for aspiring clinical research professionals. For those who are already employed at an organization that conducts clinical trials, sometimes all it takes is to “just ask,” as one respondent phrased it. This might entail a 30-minute call about what clinical trials are about, or you may even have the opportunity to shadow someone on their daily tasks. For one respondent, the importance of networking is found in seeking good mentors that will help you grow.

As far as education goes, there are a variety of courses, certificates, and certifications{3} from for-profit or higher education sources of learning, ranging from small extension programs to undergraduate or graduate degree offerings. Probably the most obvious early step involves becoming certified in GCP (Good Clinical Practice); however, there are additional courses that are available that can further immerse one’s knowledge in specific topics such as site monitoring or trial management.

Clinical research is still a developing field, and while the pathway to becoming a CRA can be frustrating, the experiences of today’s CRAs demonstrate that persistence can pay off.

References

- Francis M, Pucker A. 2023. Career Navigation in Contract Research Organizations: A Vignette. Clinical Researcher 37(4). https://acrpnet.org/2023/08/career-navigation-in-contract-research-organizations-a-vignette/

- Association of Clinical Research Professionals. 2022. Ready, Set, Clinical Research! https://acrpnet.org/employer-resources/our-services/acrp-partners-advancing-the-clinical-research-workforce/help-build-a-diverse-research-ready-workforce/

- ACRP Blog. 2024. Did You Know?: Certificates and Certifications Are Not the Same. https://acrpnet.org/2024/06/04/did-you-know-certificates-and-certification-are-not-the-same

Anthony Chew, MS, (LinkedIn) is a recent graduate of the Medical Product Development Management program at San Jose State University and currently serves as a Clinical Trial Specialist in the medical device industry for blood-based screening tests.