Clinical Researcher—June 2025 (Volume 39, Issue 3)

SPECIAL FEATURE

Thesla Berne-Anderson, EdD; Justin Scott Brathwaite, MBA; Steven Sims, MS; Jonah Weltmann, BS; Benjamin Linkous, BS; Andrés Gil Arana, BS; Aihua Wang, PhD

Addressing the Clinical Research Workforce Crisis

Clinical trials are the backbone of medical advancement, providing the evidence needed to bring novel therapies to patients. At the heart of every trial is the principal investigator (PI), whose expertise ensures both the scientific integrity of studies and the safety of participants.{1,2} However, the United States is facing a critical shortage of clinical research physicians along with a clinical research staffing crisis that threatens the future of medical innovation.{1–3} Recent studies have documented a 41% decrease in available PIs at clinical trial sites, with two-thirds of sites reporting persistent staffing challenges.{4}

At the same time, the number of registered clinical trials has soared, reaching more than 515,000 globally in 2024.{5} This surge in research activity is intensifying the demands on a shrinking workforce, leading to burnout and high turnover, while jeopardizing the pace of drug and device development.

One particularly concerning trend is the “one-and-done” phenomenon, where PIs lead a single clinical trial to never assume the role again.{3} Moreover, evidence shows that 40% of U.S. PIs participated in a single industry-sponsored trial over three years, with most trials being conducted by a modest group of experienced investigators.{6}

While the root cause underlying the one-and-done phenomena is multifaceted, it is feasible that increased trial complexity is a contributing factor. For instance, in oncology, the average number of endpoints in Phase III trials rose 37% (from 19.5 to 25.8), while procedures increased 42% between 2016 and 2021.{7}

While critical investments in clinical research infrastructure and PI training are essential to supporting new clinical research investigators, a significant barrier remains—a lack of awareness of clinical research as a career option in the first place. To address ongoing challenges related to PI shortages and broader clinical research staffing, the field needs innovative and practical solutions.

Early intervention programs, already effective in increasing the number of physicians in rural areas, could potentially be adapted to provide early practical exposure to careers in clinical research. These programs, in conjunction with other methods, could be used to help bolster the future clinical research workforce.

The Need for Early Educational Interventions

Introducing clinical research concepts and opportunities to aspiring medical students is an optimal way to inspire the next generation of physician-scientists and clinical trial leaders. One promising approach is the pipeline model pioneered by Florida State University College of Medicine (FSU COM) through several specialized programs for students in different age ranges (described in the next sections).

These initiatives are designed to nurture students from middle school through college, providing academic support, mentorship, and hands-on experiences that prepare them for rigorous careers in medicine and clinical research. They focus on introducing students to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and healthcare careers at an early stage—a strategy supported by evidence for enhancing student persistence and success.{8}

SSTRIDE: Building the Pipeline

SSTRIDE (Science Students Together Reaching Instructional Diversity and Excellence) was founded in 1993 by the lead author of this article as part of FSU COM’s mission to address the shortage of primary care physicians in the state of Florida and train physicians to provide service to rural and underserved communities.{9}

Recognizing the importance of early intervention, SSTRIDE targets students as early as middle school, offering honors science courses during the school day, after-school enrichment, standardized test prep, and clinical shadowing.{9} The program’s multifaceted approach ensures continuous academic and personal development, keeping students engaged and motivated throughout their educational journey.

Over the past three decades, the SSTRIDE program has served 2,816 middle and high school students.{10} Of the tracked alumni, 94% (n = 1,492) successfully entered college, with the majority pursuing STEM or health-related majors. By 2024, 32 alumni had matriculated into medical school, and 160 had entered graduate programs—56% of whom (n = 89) majored in STEM or healthcare fields.{11}

The program’s success is rooted in its comprehensive support network, which includes medical school deans, school district administrators, teachers, other educators, parents, community members, medical, premedical, and graduate student mentors. Through hands-on labs, field trips, guest speakers, and clinical shadowing, students gain practical insights into medical and scientific careers, while also developing fundamental scientific knowledge and research skills for future success.{9}

USSTRIDE and the Community of Practice Model

As students progress to college, they can join SSTRIDE Connect as freshmen and USSTRIDE (Undergraduate SSTRIDE) for their sophomore to senior years. The program was founded by Dr. Thesla Anderson in 1994. Over the past three decades, it has served 912 undergraduate students from FSU, Tallahassee Community College, and Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. By 2024, USSTRIDE has supported 379 students in successfully matriculating into medical school. Separately, 175 alumni have entered graduate programs, with 141 (80.6%) pursuing degrees in STEM or health science-related fields.{12}

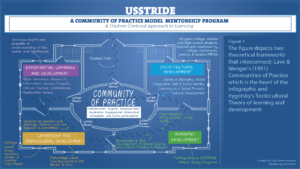

USSTRIDE is built on a Community of Practice (CoP) model, fostering a collaborative environment where students learn from peers, mentors, and faculty (see Figure 1). High-achieving juniors and seniors serve as Peer Group Leaders (PGLs), facilitating academic support, study groups, and workshops, while also mentoring underclassmen.{9}

The CoP model emphasizes sociocultural, academic, leadership, and professional development, preparing students not only for medical school but also for the demands of clinical research. Support services include tutoring, success coaching, leadership development, premedical advising, clinical shadowing, application review, mock interviews, and test preparation. This holistic approach ensures that students develop the skills, confidence, and resilience needed to thrive in challenging academic and professional environments.{9}

Figure 1: Community of Practice Model

Expanding Clinical Research Education: Bridging Academia and Industry

Recognizing the urgent need to expand the clinical research workforce, USSTRIDE is evolving to provide direct exposure to clinical research careers in both academia and industry. Through partnerships with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, students will participate in workshops, case studies, and paid internships, gaining firsthand experience in clinical trial operations.

A new training module focused on decentralized clinical trials will equip students with the skills needed to conduct remote studies effectively. The curriculum covers regulatory compliance, patient privacy, remote monitoring technologies, and telehealth platforms. Moreover, it will also involve hands-on simulations and case studies will prepare students for real-world challenges, ensuring students are ready to contribute to high-quality, patient-centered research.

USSTRIDE will also collaborate with pharmaceutical partners and include a curriculum that will expose students to regulatory requirements, institutional review board submissions, informed consent, and clinical trial operations. Hands-on training in industry settings will prepare students for entry-level roles in clinical research.

By integrating academic and industry perspectives, USSTRIDE aims to create a research-ready workforce capable of meeting the evolving needs of clinical trials.

Broader Implications and the Path Forward

The clinical research workforce crisis requires coordinated solutions. Academic institutions, industry partners, and regulatory agencies must collaborate to build a strong professional identity for clinical research, ensure equitable access to education and training, and adopt competency-based hiring practices. Programs like SSTRIDE and USSTRIDE demonstrate that early intervention, sustained mentorship, and comprehensive support can successfully prepare students for careers as physicians, physician-scientists, and clinical trial investigators. By expanding these models and forging new partnerships, we can address workforce shortages, improve access to clinical trials, and accelerate the development of new therapies.

Conclusion

The future of clinical research depends on a robust and well-trained workforce. SSTRIDE and USSTRIDE offer a proven blueprint for cultivating the next generation of clinical trial leaders, starting from middle school and continuing through college. By emphasizing early exposure, mentorship, and practical experience, these programs are helping to close the gap in clinical research staffing and ensure that all communities benefit from advances in medical science.

As the clinical research landscape grows increasingly complex, investing in early educational programs and workforce development is not just a solution—it is a necessity. Through continued innovation and collaboration, we can shape a future where clinical trials are accessible, efficient, and staffed by dedicated professionals committed to advancing health for all.

References

- Freel SA, Snyder DC, Bastarache K, Jones CT, Marchant MB, Rowley LA, Sonstein SA, Lipworth KM, Landis SP. 2023. Now is the time to fix the clinical research workforce crisis. Clinical Trials. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10504806/

- Association of Clinical Research Professionals. 2020. Is the Clinical Trial Workforce Prepared for the Future? [White Paper] https://acrpnet.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/06/ACRP_State_of_Clinical_Research_Workforce_Report_060820.pdf

- Essink B. 2025. The Investigator’s Purpose: Addressing the PI Shortage. ACRP Blog. https://acrpnet.org/2025/05/05/the-investigators-purpose-addressing-the-pi-shortage

- Cascade E. 2025. Clinical research workforce faces growing shortages. Clinical Leader. https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/clinical-research-workforce-faces-growing-shortages-0001

- World Health Organization. 2024. Number of clinical trials by year, country, WHO region and income group (1999–2024). https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/monitoring/number-of-clinical-trials-by-year-country-who-region-and-income-group

- Glass HE, Guy A. 2022. Who Are the Active U.S. Principal Investigators? Clinical Researcher 36(6). https://acrpnet.org/2022/12/20/who-are-the-active-u-s-principal-investigators

- Favaro MA, Sassano C, Sherafat R. 2024. Enabling evidence-based study endpoint selection. Applied Clinical Trials. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/enabling-evidence-based-study-endpoint-selection

- Hapgood S, Czerniak CM, Brenneman K, Clements DH, Duschl RA, Fleer M, Greenfield D, Hadani H, Romance N, Sarama J, Schwarz C, VanMeeteren B. 2020. The importance of early STEM education. In M. S. Khine & M. A. Saleh (Eds.), Handbook of research on STEM education (pp. 87–100). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429021381-10

- Berne-Anderson T. 2023. The impact of U-SSTRIDE mentorship programs on first-generation, rural and undergraduate students’ success through a premedical track and beyond (Publication No. 31635077) [Doctoral dissertation, St. Edward’s University] ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/docview/3128706921

- Wang A. 2023. Florida State University College of Medicine Interdisciplinary Medical Science Program outcome annual report. Florida State University College of Medicine. https://med.fsu.edu/newspubs/publications/2023-24-annual-report

- Wang A. 2024. Precollege SSTRIDE outcome data [Unpublished internal report]. Florida State University College of Medicine.

- Wang A. 2024. USSTRIDE outcome data [Unpublished internal report]. Florida State University College of Medicine.

Thesla Berne-Anderson, EdD, is Founder of SSTRIDE and USSTRIDE and Executive Director of Precollege and College Programs at the Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee, Fla.

Justin Scott Brathwaite, MBA, is a Site Readiness and Regulatory Senior Specialist with Fortrea and a PhD student in clinical research at the University of Jamestown in North Dakota.

Steven Sims, MS, is an Associate Researcher with the Department of Pharmacological Sciences in the Center for Translational Medicine and Pharmacology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Jonah Weltmann, BS, is a pre-medical student in the College of Arts & Sciences at Florida State University.

Benjamin Linkous, BS, is a fourth-year medical student at the Florida State University College of Medicine.

Andrés Gil Arana, BS, is a PhD Student at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

Aihua Wang, PhD, is Director of Program Evaluation at the Florida State University College of Medicine.