Clinical Researcher—May 2021 (Volume 35, Issue 4)

PRESCRIPTIONS FOR BUSINESS

Jonathan Andrus

The global COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on clinical trials everywhere. By February 2021, research by GlobalData{1} indicates clinical trials being conducted by more than 1,100 U.S. and European organizations were adversely affected. As a result, virtual clinical trials and bring-your-own-device (BYOD) clinical trial models have come into their own.

BYOD, a strategy of installing electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) tools on patients’ own devices, has been in use for years. However, by necessity, the ongoing public health crisis has resulted in faster, broader support for this powerful, patient-centric clinical data-capture solution.

When 81% of Americans own smartphones and are more likely to use them reliably than provisioned devices,{2} it makes sense to incorporate personal devices into clinical trials wherever feasible. The result is often shorter timelines and more cost-efficient clinical trials that yield better data through simplified ePRO collection that is less of a burden on patients.

This article addresses considerations for ensuring a successful BYOD strategy at all clinical trial stages.

Let Your Patients Choose

Patients are crucial in clinical trials. To encourage clinical trial enrollment and retention, we need to understand patient needs, desires, and dislikes. Do patients want BYOD? Is it always suitable?

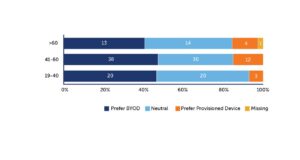

Several years back, a study by Clinical Ink with ICON and Novartis found that 45% of clinical trial participants preferred a BYOD approach over using a provisioned device. About 40% didn’t have a preference and would have been happy with BYOD or a provisioned device. Only 15% preferred a provisioned device (see Figure 1). Even among patients over 60, more than 82% would have accepted BYOD.{2}

Figure 1: 45% of Subjects Found BYOD More Convenient Compared to 15% Who Preferred a Provisioned Device and 40% Who Had No Preference

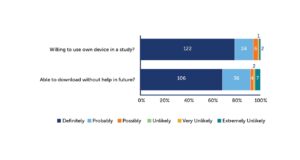

We then asked about patients’ ease in using their smartphones. For instance, would they feel comfortable if we asked them to download an app?

The result was clearly in favor of BYOD. Around 90% to 95% of patients were willing to use their own device in a study, and the vast majority also believed they would be able to download the app without assistance (see Figure 2). Downloading an app does not appear to be a great barrier. Most participants would likely not require assistance.

Figure 2: Most Patients Are Willing to Use Their Own Device and Able to Download an App for a Clinical Study

Knowing that older patients might be less comfortable with technology in general, we wondered what we could offer that might help. One finding was that older patients tend to have bigger devices with larger screens. We realized we were making it more unattractive for some patients by asking them to use a device they are not familiar with and that has a smaller screen than they’re used to. This suggests that providing larger devices with bigger screens for these patients might make it easier for them to participate and remain in a study.

Overall, to maximize enrollment and retention, we need to do our research and develop systems and processes that allow patients as much choice as possible in how they participate and provide us with their data. In the case of BYOD, the majority of patients are already on board. For those who are not, we can provide devices.

Understanding the Regulations for BYOD

What do the regulators say about BYOD? Officially, not much. From the compliance perspective, the 2017 Q&A document 21 CFR Part 11 from the Code of Federal Regulations{3} does not differentiate between BYOD and provisioned devices. However, anecdotally, certain concerns have come to light in private communications and conversations with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These concerns fall into three categories:

- Data privacy

- Inclusivity (we don’t want to exclude any patients due to the lack of an adequate device)

- Technical considerations

The first and last points can be addressed through existing technology solutions on a study-by-study basis. Regarding inclusivity, it’s important to remember that when we talk about a BYOD trial, it’s never 100% BYOD. You will always need to provide a few devices to support patients who can’t bring their own and possibly help with data plans as needed.

Concerns we don’t hear at this point from the FDA are about the equivalence of paper and other kinds of questionnaires to BYOD. Crossover studies{2} have demonstrated that equivalence is generally not a problem. In addition, there is a push by the FDA to move away from paper-based trials.

Lastly, though we continue to make the technology more sophisticated, fundamentally, BYOD is not new. We’ve used interactive web response systems (IWRS) in ePRO for a long time. Common concerns, such as what happens to data if a patient loses their device, deletes the app, upgrades their phone, or has insufficient bandwidth have been put to rest. The apps are different now, but the concept is the same.

To date, numerous studies have made successful regulatory submissions with BYOD-captured primary endpoint data. While BYOD is not suitable for every situation, many Phase I–III studies can benefit from greater feasibility, faster recruitment, and better retention with significant savings in time and cost by taking a BYOD approach.

An Illustration: Leading Firm Switches to BYOD Mid-Trial

Mid-pandemic, a leading pharmaceutical company conducting traditional Phase II and III trials needed to pivot quickly to allow 2,000 patients at more than 250 sites to report outcomes from home for central nervous system (CNS) studies, using their own devices.

The Ask:

- Handle CNS-related protocols with many standardized assessments and scales.

- Design, develop, and deploy ePRO for four studies—two in Phase II and two in Phase III.

- Enable patients to use their own devices (BYOD).

- Provide alternatives for patients unable to participate by BYOD means.

- Execute the changeover in data collection practices rapidly.

The Answer:

- Design, develop, and deploy four studies in 10 days.

- Build 10 different collection forms for home use (SF-36, HADS, LEC-5, etc.).

- Get early buy-in from license holders to prevent bottlenecks.

- Create engagement content for all four studies.

- Perform agile study development with limited user acceptance testing.

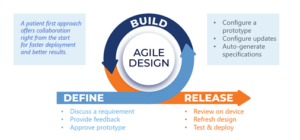

In our experience, driving collaboration from the start is the best way to deploy faster and ensure user-friendly results. This patient-centric, BYOD setup helped improve patient retention and pave the way for enrollments at a time when no one wanted to visit a clinic.

Rapid, Agile, Collaborative Study Development

The ability to build all the patient-completed forms and engagement content in 10 days for all four studies relied on an agile design and development process (see Figure 3).

This approach does require a lot of coordination. After initial discussion of requirements, an agile BYOD design effort moves quickly to configuration of a prototype. Both teams gather—in this case, virtually—for the collaborative effort. Design and project management teams walk the sponsor team through the design to make sure its members have been able to download the study app onto their own phones. An interactive user acceptance testing meeting follows.

The sponsor team provides feedback instantly to the build team. The build team immediately refreshes the design and redeploys it to be tested again. This iterative design and development process yields a high-performing, pressure-tested, ready-to-deploy build in a very short time. Once the final updates are made, the specifications are generated.

Figure 3: An Agile eSource Ecosystem Build Design

In all, an agile methodology:

- Means build first and output the specifications after the fact.

- Requires team members to be available to review interactively.

- Allows for a configurable, immediate, and interactive build.

- Involves immediate updates, based on feedback.

- Is tech-transfer-enabled.

This approach has been used in more than 100 studies across varied therapeutic areas.

Adherence, Retention, and Data Quality Hinge on Engagement

BYOD is a channel not only for collecting patient-reported outcomes, but also for communicating directly with patients. Because people tend to keep their own smartphones with them most of the time, it is a reliable tool. Beyond ePRO, a patient’s device can be used to:

- Schedule event diaries, such as a dosing diary.

- Present simple to-do lists.

- Provide task reminders.

- Send upcoming visit reminders.

- Offer fast facts about the study, including goals and objectives.

- Thank them for taking the time and making the effort to participate.

Messaging and reminders help keep patients engaged in a study and improve their likelihood of reliably fulfilling protocol requirements.

Realize BYOD Can Be an Efficient Strategy

Certainly, patient centricity in clinical trials and elsewhere is in fashion as well as being a current interest of the FDA. More than these considerations, it eases enrollment by making trials more attractive for patients.

As the quintessential, patient-preferred solution, BYOD also helps with retention and more complete data collection by alleviating the burdens of ePRO and increasing the likelihood that reminders and other patient engagement strategies will be received in a timely fashion.

Furthermore, as part of the decentralized trial toolkit, BYOD allows broad and diverse patient participation as it always includes the option of provisioned devices for patients unable to take advantage of BYOD. Finally, with an agile, rapid build strategy, sponsors can maintain or even reduce timelines—all while saving money on smartphone purchases. For a large trial, this can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

References

- GlobalData. 2021. COVID-19 Executive Briefing: Understanding the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the implications for the healthcare sector. Pharma Technology Focus. https://pharma.nridigital.com/pharma_jun20/covid-19_executive_briefing_by_globaldata

- Byrom B, Doll H, Muehlhausen W, et al. 2018. Measurement Equivalence of Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Response Scale Types Collected Using Bring Your Own Device Compared to Paper and a Provisioned Device: Results of a Randomized Equivalence Trial. Value in Health 21(5):581–9. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S109830151733615X

- FDA.gov. Use of Electronic Records and Electronic Signatures in Clinical Investigations Draft Guidance Q&A. FDA-2017-D-1105. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/use-electronic-records-and-electronic-signatures-clinical-investigations-under-21-cfr-part-11

Jonathan Andrus is Chief Business Officer for Clinical Ink.